The 1950s has always been the most fascinating era of fandom for us -- it was truly

a Golden Age, when conventions were of manageable size, international ties were

growing, and subfandoms hadn't yet fractured away. It was also a time of FIAWOL,

when fans lived for the next issues of Hyphen, Quandry, and

Shaggy, theorized about "Who sawed Courtney's boat?", were croggled by the

non-existence of Joan W. Carr and Carl Brandon, and campaigned for "South Gate in

`58." Back then, many of today's writers and scientists were fans who had yet to

sell a single word of fiction or conduct a single thought experiment. The next

article is a remembrance from that era, as well as a window onto a fandom that even

today, here in North America, we hear little about, by two fans who have gone on to

much bigger and brighter things.

The 1950s has always been the most fascinating era of fandom for us -- it was truly

a Golden Age, when conventions were of manageable size, international ties were

growing, and subfandoms hadn't yet fractured away. It was also a time of FIAWOL,

when fans lived for the next issues of Hyphen, Quandry, and

Shaggy, theorized about "Who sawed Courtney's boat?", were croggled by the

non-existence of Joan W. Carr and Carl Brandon, and campaigned for "South Gate in

`58." Back then, many of today's writers and scientists were fans who had yet to

sell a single word of fiction or conduct a single thought experiment. The next

article is a remembrance from that era, as well as a window onto a fandom that even

today, here in North America, we hear little about, by two fans who have gone on to

much bigger and brighter things.

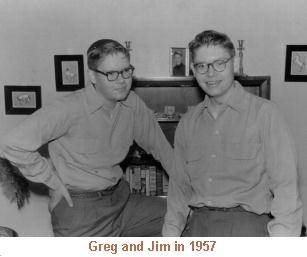

Jim

I have looked back at my collection

of the early Void, produced almost 50 years ago when we were young and the

world was new. There was a great future out there. I look back upon these early

manifestations, our first organized publications. Thinking about 'Gerfandom', the

term now obsolete, I can't help thinking of it as our early origins, early

selves. I have looked back at my collection

of the early Void, produced almost 50 years ago when we were young and the

world was new. There was a great future out there. I look back upon these early

manifestations, our first organized publications. Thinking about 'Gerfandom', the

term now obsolete, I can't help thinking of it as our early origins, early

selves.

We came to Germany in 1955 and found

it a forbidding land. We produced issues of Void using first hectograph and

later a mimeo. It was a daunting time; there were few fans in Europe and we, having

just come from the U.S., carried a basic fannish viewpoint, which was alien to the

serious SF viewpoint point of the Europeans. We had produced a carbon-copied

zine, Vacuum, at age 13 while still in Atlanta, but the title seemed not

quite right. The issues of Void that we produced as mature 14-year-olds were

in the beginning composed entirely of reviews, in comments written entirely by the

two of us. (On rereading them, they are better now than they seemed at the time.)

In that time, there was a substantial fandom in the U.S. and a burgeoning U.K.

fandom. But on the Continent, all was essentially dark in fannish terms. You have

to remember that the Cold War had succeeded the collapse of European prosperity

during WWII and that living was quite austere. We came to Germany in 1955 and found

it a forbidding land. We produced issues of Void using first hectograph and

later a mimeo. It was a daunting time; there were few fans in Europe and we, having

just come from the U.S., carried a basic fannish viewpoint, which was alien to the

serious SF viewpoint point of the Europeans. We had produced a carbon-copied

zine, Vacuum, at age 13 while still in Atlanta, but the title seemed not

quite right. The issues of Void that we produced as mature 14-year-olds were

in the beginning composed entirely of reviews, in comments written entirely by the

two of us. (On rereading them, they are better now than they seemed at the time.)

In that time, there was a substantial fandom in the U.S. and a burgeoning U.K.

fandom. But on the Continent, all was essentially dark in fannish terms. You have

to remember that the Cold War had succeeded the collapse of European prosperity

during WWII and that living was quite austere.

We began Void and quickly

obtained lots of articles from British fans like Ron Bennett, Archie Mercer, Walt

Willis, Eric Bentcliffe and John Berry. We quickly got responses from American fans

Terry Carr, Dick Ellington, Dick Geis, Joe Gibson. And then there were the

continentals Julian Parr, Lars Helander, Jan Jansen. The British artists helped --

Arthur Thomson, Eddie Jones, Terry Jeeves. Julian Parr, who was with the British

Foreign Service, was a steady contributor of reviews of European prozines. We began Void and quickly

obtained lots of articles from British fans like Ron Bennett, Archie Mercer, Walt

Willis, Eric Bentcliffe and John Berry. We quickly got responses from American fans

Terry Carr, Dick Ellington, Dick Geis, Joe Gibson. And then there were the

continentals Julian Parr, Lars Helander, Jan Jansen. The British artists helped --

Arthur Thomson, Eddie Jones, Terry Jeeves. Julian Parr, who was with the British

Foreign Service, was a steady contributor of reviews of European prozines.

We adopted an early European

orientation based on the models of fannish fandom from stateside. It was a unique

experience. Having absorbed fannish attitudes in the U.S. just before we left, we

communi-cated them into Europe. This gave us a basically iconoclastic view of the

somewhat insufferable seriousness of the early German fans such as Walt Ernsting and

Anne Steul. (Germany's leading SF writers were producing 1930s style space opera

epitomized by Perry Rhodan -- like Doc Smith without the style.) We adopted an early European

orientation based on the models of fannish fandom from stateside. It was a unique

experience. Having absorbed fannish attitudes in the U.S. just before we left, we

communi-cated them into Europe. This gave us a basically iconoclastic view of the

somewhat insufferable seriousness of the early German fans such as Walt Ernsting and

Anne Steul. (Germany's leading SF writers were producing 1930s style space opera

epitomized by Perry Rhodan -- like Doc Smith without the style.)

A fine example of our approach occurs

in Void 6 in Greg's "Deutsch Derogation." The derogation was a form invented

by Boyd Raeburn in his legendary fanzine A Bas. It's a marvelous method of

sending up people, using their own words, and should be reintroduced to fandom. As

Greg said at the introduction, "we will show all of you the real atmosphere of

goodwill in which Gerfandom works and so you might see the real cooperation we have

here." Of course the dialogue among various participants, some quoted from their

works, some made up, shows them to be all self-centered, egocentric, and short

sighted. A bit surprising, then, that German fans were speaking to us after

that. A fine example of our approach occurs

in Void 6 in Greg's "Deutsch Derogation." The derogation was a form invented

by Boyd Raeburn in his legendary fanzine A Bas. It's a marvelous method of

sending up people, using their own words, and should be reintroduced to fandom. As

Greg said at the introduction, "we will show all of you the real atmosphere of

goodwill in which Gerfandom works and so you might see the real cooperation we have

here." Of course the dialogue among various participants, some quoted from their

works, some made up, shows them to be all self-centered, egocentric, and short

sighted. A bit surprising, then, that German fans were speaking to us after

that.

As usual, the underlying tension was

between the serious forward-looking and the iconoclastic humorous fans. The sercons

were imbued with the feeling that the future was accessible, but only to serious

folks. This is a worldview now largely extinct. The alternative view, which we

held, was that everything was for fun, transient and up for grabs -- the basic

fannish attitude. In all the Voids, this iconoclastic attitude really comes

out. I think that the early Voids encapsulated an attitude in isolation on

the continent that was taken up and carried on by those later to be co-editors of

Void. [One odd feature of this attitude: fannish fans claimed to be a bit

above reading SF, leaving it to the serious types. But we really did read

quite a lot, and cared about it. We were Heinlein fans and thought the future would

belong to those who prepared for it. And that's exactly what we did later in

life.] As usual, the underlying tension was

between the serious forward-looking and the iconoclastic humorous fans. The sercons

were imbued with the feeling that the future was accessible, but only to serious

folks. This is a worldview now largely extinct. The alternative view, which we

held, was that everything was for fun, transient and up for grabs -- the basic

fannish attitude. In all the Voids, this iconoclastic attitude really comes

out. I think that the early Voids encapsulated an attitude in isolation on

the continent that was taken up and carried on by those later to be co-editors of

Void. [One odd feature of this attitude: fannish fans claimed to be a bit

above reading SF, leaving it to the serious types. But we really did read

quite a lot, and cared about it. We were Heinlein fans and thought the future would

belong to those who prepared for it. And that's exactly what we did later in

life.]

I remember those years in that German

house, maintaining paper contact with like-minded fans thousands of miles away. We

used hecto, then a locally-bought flatbed mimeo, then a Sears Roebuck rotary that

had been mail-ordered from the USA. Fandom and science fiction formed for us a

lifeline and focused our ideas of the world. The early Void was essential to

our development and a lot of fun. We learned many skills in producing something on

schedule. Later, I would use those skills to produce proposals and reports in the

R&D industry. Compared to fanzines, that was easy. In fact, it had a real impact

on my career. Being able to integrate a collection of documents into a coherent

whole, proposals, final reports, etc., was one cause of my rapid advancement in

research. I remember those years in that German

house, maintaining paper contact with like-minded fans thousands of miles away. We

used hecto, then a locally-bought flatbed mimeo, then a Sears Roebuck rotary that

had been mail-ordered from the USA. Fandom and science fiction formed for us a

lifeline and focused our ideas of the world. The early Void was essential to

our development and a lot of fun. We learned many skills in producing something on

schedule. Later, I would use those skills to produce proposals and reports in the

R&D industry. Compared to fanzines, that was easy. In fact, it had a real impact

on my career. Being able to integrate a collection of documents into a coherent

whole, proposals, final reports, etc., was one cause of my rapid advancement in

research.

Those early days have far more

influence than we realized at the time. After graduate school, Greg and I undertook

our separate careers. I worked in R&D and Greg went on to become a professor.

In recent years, we've begun to work together again and are now working on all sorts

of fascinating things: devising a new form of aero/spacecraft, figuring out what

sort of beacons advanced civilizations could make, doing flight experiments using

beam-driven sails and planning to use beams from Earth hitting spacecraft in orbit

to propel them. Those early days have far more

influence than we realized at the time. After graduate school, Greg and I undertook

our separate careers. I worked in R&D and Greg went on to become a professor.

In recent years, we've begun to work together again and are now working on all sorts

of fascinating things: devising a new form of aero/spacecraft, figuring out what

sort of beacons advanced civilizations could make, doing flight experiments using

beam-driven sails and planning to use beams from Earth hitting spacecraft in orbit

to propel them.

I wonder what our earlier selves

would have thought of this now-real future? It would've seemed quite fantastic, and

I think those earlier selves would be quite pleased with what we have become. I wonder what our earlier selves

would have thought of this now-real future? It would've seemed quite fantastic, and

I think those earlier selves would be quite pleased with what we have become.

Greg

Greg

Hell, we even still belong to an

APA. Hell, we even still belong to an

APA.

And what became of all those figures?

Julian Parr is retired, still living in Germany. The early SF pros have left the

scene. Jan Jansen immigrated to the U.S. and vanished from fandom. Walter Ernsting,

editor of the first German SF magazine, had come from a dramatic background -- a

soldier captured at Stalingrad, worked in a Gulag camp for five years, then

repatriated. All that, and within a few years he was editing SF! Anne Steul,

energetic and vastly overweight, kept active in fandom, even visiting a UK

convention. (Prompting a Hyphen bacquote, "She Annesteuled herself in the

kitchen.") She died several decades ago. And what became of all those figures?

Julian Parr is retired, still living in Germany. The early SF pros have left the

scene. Jan Jansen immigrated to the U.S. and vanished from fandom. Walter Ernsting,

editor of the first German SF magazine, had come from a dramatic background -- a

soldier captured at Stalingrad, worked in a Gulag camp for five years, then

repatriated. All that, and within a few years he was editing SF! Anne Steul,

energetic and vastly overweight, kept active in fandom, even visiting a UK

convention. (Prompting a Hyphen bacquote, "She Annesteuled herself in the

kitchen.") She died several decades ago.

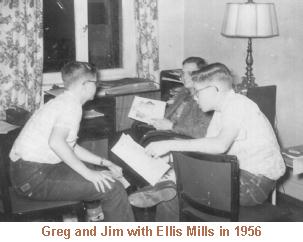

That era still lives in Gerfandom

history. Occasionally a German-language fanzine comes in the mail, sometimes with

pictures from that era. Apparently Ellis Mills, the Air Force sergeant who dabbled

in fandom, died in the 1990s. The other American who flashed briefly across the

fannish horizon was Mike Gates, who was in high school with us and caught the bug.

He even published one issue of a fanzine, using the name I gave him, Motley.

Gates was neurotic, high-energy, and ate incessantly. He came over to our house

every day to "fan" (he insisted it was a verb). This led to another Hyphen

bacquote, "We introduced him to fandom and he came over and ate all the crabapples

off our tree." The son of a general, whereas our father was a mere colonel (but a

real combat officer, World War II and Korea, which mattered a lot to us), Gates

always tried to pull rank in his roundabout way, and let everybody know that he was

going to rise fast in the Army when he got the chance. About five years later he

was arrested for impersonating an officer, complete with an accurate uniform. We

never heard from him again. That era still lives in Gerfandom

history. Occasionally a German-language fanzine comes in the mail, sometimes with

pictures from that era. Apparently Ellis Mills, the Air Force sergeant who dabbled

in fandom, died in the 1990s. The other American who flashed briefly across the

fannish horizon was Mike Gates, who was in high school with us and caught the bug.

He even published one issue of a fanzine, using the name I gave him, Motley.

Gates was neurotic, high-energy, and ate incessantly. He came over to our house

every day to "fan" (he insisted it was a verb). This led to another Hyphen

bacquote, "We introduced him to fandom and he came over and ate all the crabapples

off our tree." The son of a general, whereas our father was a mere colonel (but a

real combat officer, World War II and Korea, which mattered a lot to us), Gates

always tried to pull rank in his roundabout way, and let everybody know that he was

going to rise fast in the Army when he got the chance. About five years later he

was arrested for impersonating an officer, complete with an accurate uniform. We

never heard from him again.

I carried away from the Gerfandom

days an appreciation for the subtleties of writing, for craft and setting scenes.

I learned that I really liked writing -- a skill that led to my taking all my

required university English courses by exam; just write an essay and collect the

credit. I carried away from the Gerfandom

days an appreciation for the subtleties of writing, for craft and setting scenes.

I learned that I really liked writing -- a skill that led to my taking all my

required university English courses by exam; just write an essay and collect the

credit.

Dad's next assignment was commander

of the National Guard, based in Dallas, and we approached Dallas fandom in the same

spirit, satirizing classic fuggheads like Rich Koogle. By this time we had become

Smartass R Us, and must've been unbearable to the more sober Texas fans. Mercifully,

they looked the other way. Tom Reamy I remember for his saintly reserve. I never

suspected that he would become a major fantasy writer. By that time I was thinking

of pursuing writing as a profession. I went to my father and said, "Dad, I know the

military is a good, solid career, but I want to grow up and become a science fiction

writer." Dad's next assignment was commander

of the National Guard, based in Dallas, and we approached Dallas fandom in the same

spirit, satirizing classic fuggheads like Rich Koogle. By this time we had become

Smartass R Us, and must've been unbearable to the more sober Texas fans. Mercifully,

they looked the other way. Tom Reamy I remember for his saintly reserve. I never

suspected that he would become a major fantasy writer. By that time I was thinking

of pursuing writing as a profession. I went to my father and said, "Dad, I know the

military is a good, solid career, but I want to grow up and become a science fiction

writer."

He shook his head sadly and replied,

"Sorry, son, but you can't do both." Maybe he was right; I still haven't really

grown up, and that helps while writing fiction. Shortly after that, I read Laura

Fermi's Atoms in the Family, the biography of her famous physicist husband

Enrico, and that changed my life. I saw that you could do science and have a hell

of a lot of pure creative fun. It was certainly a lot easier to aim for than being

the captain of a spaceship. He shook his head sadly and replied,

"Sorry, son, but you can't do both." Maybe he was right; I still haven't really

grown up, and that helps while writing fiction. Shortly after that, I read Laura

Fermi's Atoms in the Family, the biography of her famous physicist husband

Enrico, and that changed my life. I saw that you could do science and have a hell

of a lot of pure creative fun. It was certainly a lot easier to aim for than being

the captain of a spaceship.

Still, Dallas fans were fun, and we

helped with the first con in Texas, in Dallas 1958. (Having helped run the first

German con in Wetzlar in 1956. This has got to be the most drastic transition in

con-giving annals. We'd learned, though -- and never worked on cons again.) Still, Dallas fans were fun, and we

helped with the first con in Texas, in Dallas 1958. (Having helped run the first

German con in Wetzlar in 1956. This has got to be the most drastic transition in

con-giving annals. We'd learned, though -- and never worked on cons again.)

We returned to the U.S. in October

1957. On board the America, a classy ship, I was enjoying morning soup

served on deck when the morning's ship newspaper came by. Big headlines about

Sputnik's launch. I recall gasping and running down the deck to find Jim. That

marked the end of an era. For us, the electrifying news brought the dawning

knowledge that we could have careers in science, that the future was opening in a

way SF had foreseen. We returned to the U.S. in October

1957. On board the America, a classy ship, I was enjoying morning soup

served on deck when the morning's ship newspaper came by. Big headlines about

Sputnik's launch. I recall gasping and running down the deck to find Jim. That

marked the end of an era. For us, the electrifying news brought the dawning

knowledge that we could have careers in science, that the future was opening in a

way SF had foreseen.

All illustrations by Steve Stiles

All photos by Eloise Benford

|