After readlng some of the letters of

comment on Mimosa 6, it occurs to us that we never did explain some of the

fannish references in Teddy Harvia's wonderful wrap-around cover from last issue.

Several people asked us about it, among them Dave Kyle, who wrote "I've puzzled over

the wrap-around cover artwork because it seems to be loaded with symbols which I only

half understand," and Jeanne Mealy who asked, "Do I detect brooding presences in the

cover?" Well yes, there was some symbolism in the covers, starting with

the observation that the difference between the wilds of Tennessee and the Washington

metro area is like night (back cover) and day {front cover). Beyond that, the back cover

features a Mimosa tree, symbolic of this fanzine, and a saber-toothed tiger, a reminder

of our previous fanzine. Some of you readers may be familiar with that other fanzine,

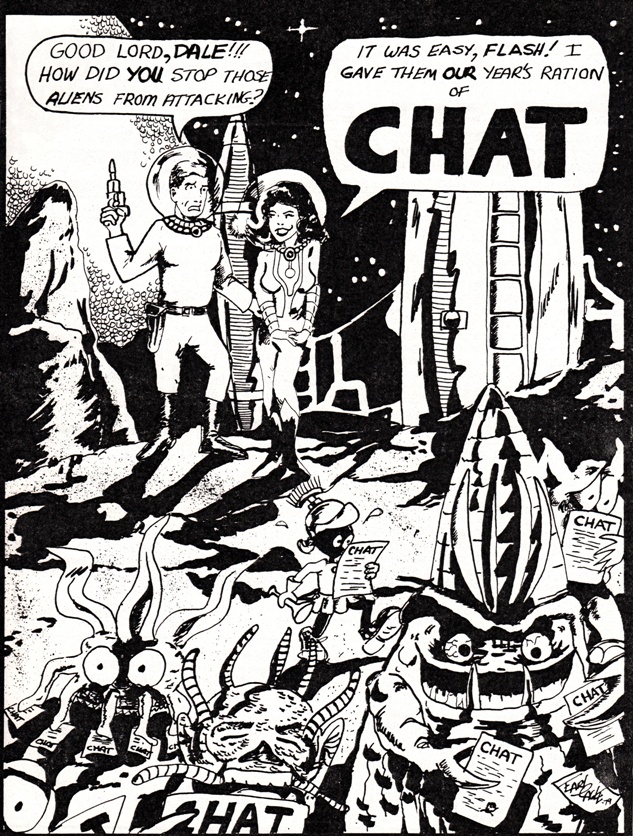

Chat, which we published every month from 1977 to 1981. It was ostensibly set

up to be the newszine/clubzine of the local Chattanooga SF organization, but it managed

to take on a life of its own and eventually became much more than just a clubzine like

Anvil and FOSFAX seem to have done. But what, you ask, was the

significance of the saber-toothed tiger? Well, this will all be explained, and more.

Read on... After readlng some of the letters of

comment on Mimosa 6, it occurs to us that we never did explain some of the

fannish references in Teddy Harvia's wonderful wrap-around cover from last issue.

Several people asked us about it, among them Dave Kyle, who wrote "I've puzzled over

the wrap-around cover artwork because it seems to be loaded with symbols which I only

half understand," and Jeanne Mealy who asked, "Do I detect brooding presences in the

cover?" Well yes, there was some symbolism in the covers, starting with

the observation that the difference between the wilds of Tennessee and the Washington

metro area is like night (back cover) and day {front cover). Beyond that, the back cover

features a Mimosa tree, symbolic of this fanzine, and a saber-toothed tiger, a reminder

of our previous fanzine. Some of you readers may be familiar with that other fanzine,

Chat, which we published every month from 1977 to 1981. It was ostensibly set

up to be the newszine/clubzine of the local Chattanooga SF organization, but it managed

to take on a life of its own and eventually became much more than just a clubzine like

Anvil and FOSFAX seem to have done. But what, you ask, was the

significance of the saber-toothed tiger? Well, this will all be explained, and more.

Read on...

- - - - - - - -

Visit to a Small Fanzine --

the Life and Times of

Chat

by Dick & Nicki Lynch

by Dick & Nicki Lynch

We don't know what originally possessed us

with the idea of doing a fanzine. It was early autumn in 1977, and we had just lost a bid

to hold the 1978 DeepSouthCon in Chattanooga, which had left a bad taste in our mouths from

the way the winning campaign had been conducted. All that is now water long ago gone under

the bridge, but at the time we remember it was like being all dressed up with no place to

go -- creative energy was present, looking for an outlet now that chairing a convention was

no longer in the cards. At any rate, the local SF club, the Chattanooga SF Association (or

CSFA) was fairly new and growing. There was a need for some kind of central focus, and out

of all that Chat was conceived. We don't know what originally possessed us

with the idea of doing a fanzine. It was early autumn in 1977, and we had just lost a bid

to hold the 1978 DeepSouthCon in Chattanooga, which had left a bad taste in our mouths from

the way the winning campaign had been conducted. All that is now water long ago gone under

the bridge, but at the time we remember it was like being all dressed up with no place to

go -- creative energy was present, looking for an outlet now that chairing a convention was

no longer in the cards. At any rate, the local SF club, the Chattanooga SF Association (or

CSFA) was fairly new and growing. There was a need for some kind of central focus, and out

of all that Chat was conceived.

It was Nicki who came up with the name, a

double-entendre from the zine's purpose (club news) and place of origin (Chattanooga). There

was some opposition to the idea from a couple of CSFA members who claimed that it cou1dn't

possibly help the club and would be a drain on its meager resources. But most members

embraced the idea, and in October 1977 the first issue appeared. It was Nicki who came up with the name, a

double-entendre from the zine's purpose (club news) and place of origin (Chattanooga). There

was some opposition to the idea from a couple of CSFA members who claimed that it cou1dn't

possibly help the club and would be a drain on its meager resources. But most members

embraced the idea, and in October 1977 the first issue appeared.

The first few issues of Chat were pretty

scrawny, being only two or four pages long and limited pretty much to local fan happenings

with maybe a review or two thrown in. We didn't get a letter of comment for several months,

and the first verbal comment we received was sort of a backhanded slap -- a club member told

us he already knew all the news in the issue. The first continuing feature, a monthly column

co-written by two local fans, didn't begin until Chat 7 (April 1978). During that

six-month start-up period we did most of the writing, all of the production work, and assumed

all of the production costs. Later on, quite a bit of the material published each month came

from other fans, both local and out-of-region; however, the club never really did take to the

idea that the monthly newszine could in fact be a unifying club activity. The first few issues of Chat were pretty

scrawny, being only two or four pages long and limited pretty much to local fan happenings

with maybe a review or two thrown in. We didn't get a letter of comment for several months,

and the first verbal comment we received was sort of a backhanded slap -- a club member told

us he already knew all the news in the issue. The first continuing feature, a monthly column

co-written by two local fans, didn't begin until Chat 7 (April 1978). During that

six-month start-up period we did most of the writing, all of the production work, and assumed

all of the production costs. Later on, quite a bit of the material published each month came

from other fans, both local and out-of-region; however, the club never really did take to the

idea that the monthly newszine could in fact be a unifying club activity.

Chat might well have remained at that

level of effort indefinitely, except for a spur-of-the-moment decision in February 1978 to

attend a small convention in Little Rock, Arkansas, where we met Bob Tucker. Chat might well have remained at that

level of effort indefinitely, except for a spur-of-the-moment decision in February 1978 to

attend a small convention in Little Rock, Arkansas, where we met Bob Tucker.

It's no secret that Bob Tucker has been a big

influence and encouragement to us over the years. He was a frequent guest at our house when

we lived in Chattanooga, and has been the source of several articles that have appeared in

Chat and Mimosa. The result of that first meeting was a four-page interview

which appeared in the sixth issue of Chat (March 1978), and boosted that issue's page

count to eight pages, a seemingly astronomical level of activity for us at that time. But it

turned out that after that, we would never do another issue of less than eight pages again. It's no secret that Bob Tucker has been a big

influence and encouragement to us over the years. He was a frequent guest at our house when

we lived in Chattanooga, and has been the source of several articles that have appeared in

Chat and Mimosa. The result of that first meeting was a four-page interview

which appeared in the sixth issue of Chat (March 1978), and boosted that issue's page

count to eight pages, a seemingly astronomical level of activity for us at that time. But it

turned out that after that, we would never do another issue of less than eight pages again.

That Tucker interview, in retrospect, isn't as

interesting as later things involving him we've published. We asked him what his favorite

novels were and he told us; we asked him how he came to be a writer and he told us; we asked

him what he was working on and he told us. It is to Tucker's credit (and his wit) that the

interview came out as well as it did; we didn't ask him a single question about any of the

fannish hijinks he's been involved in over the years like the Staples war or the Tucker

Hotel. The nearest thing of fan historical interest was his account of his airplane trip

to Australia for the 1975 Worldcon. He must have thought we were just a couple of neos,

and who knows -- he may have been mostly right. That Tucker interview, in retrospect, isn't as

interesting as later things involving him we've published. We asked him what his favorite

novels were and he told us; we asked him how he came to be a writer and he told us; we asked

him what he was working on and he told us. It is to Tucker's credit (and his wit) that the

interview came out as well as it did; we didn't ask him a single question about any of the

fannish hijinks he's been involved in over the years like the Staples war or the Tucker

Hotel. The nearest thing of fan historical interest was his account of his airplane trip

to Australia for the 1975 Worldcon. He must have thought we were just a couple of neos,

and who knows -- he may have been mostly right.

We eventually conducted and published much more

interesting interviews with Don Wollheim, Hal Clement, Jack Chalker, Vincent DiFate, and Jack

Williamson; there were also a couple of three-way interviews, involving us, Bob Tucker, and

other writers; one of them was with Frank Robinson and one with Robert Bloch. The Bloch

interview, from Chat 12 (September 1978), was particularly memorable, and even

today it still reads well. See for yourself... We eventually conducted and published much more

interesting interviews with Don Wollheim, Hal Clement, Jack Chalker, Vincent DiFate, and Jack

Williamson; there were also a couple of three-way interviews, involving us, Bob Tucker, and

other writers; one of them was with Frank Robinson and one with Robert Bloch. The Bloch

interview, from Chat 12 (September 1978), was particularly memorable, and even

today it still reads well. See for yourself...

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

The Two Bobs

an Interview with Bob Bloch and Bob Tucker

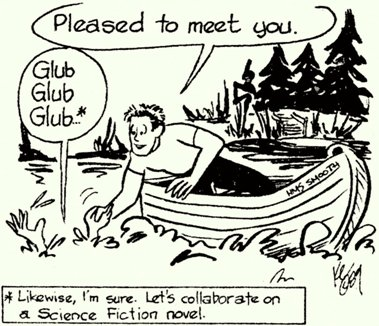

On Friday, July 28 at Rivercon, Chat had

the opportunity of meeting Robert Bloch and, with longtime friend and fellow author Bob Tucker,

discussing various remembrances. Following is a portion of that dialogue. On Friday, July 28 at Rivercon, Chat had

the opportunity of meeting Robert Bloch and, with longtime friend and fellow author Bob Tucker,

discussing various remembrances. Following is a portion of that dialogue.

Chat: Let's talk about old-time fandom.

Chat: Let's talk about old-time fandom.

Tucker: All right.

Chat: When did you meet Bob Bloch?

Tucker: In 1946. The 4th World Convention was in Los Angeles in 1946.

Pacificon it was called. And one day I was out on this lake; it was in a little

park across the street from the convention hall, and I was out there boating, taking

a break from the convention. So I was out there in a little electric boat, and lo

and behold, here comes Bob in his little electric boat. When I tell this

story, I exaggerate for effect; he really didn't ram into me, he didn't capsize me

and knock me over, but I tell that he did. That's how we met. We went back

and he told a story on the program about his typewriter, which introduced me to the

humor of Robert Bloch. He underwent a harrowing experience not too much before then,

and he was a poor struggling writer at the time. And if you remember the story,

Robert, you did something with your typewriter that you talked about in 1946.

Bloch: No. I don't even remember 1946.

Tucker: (Laughs) Well, he hocked his typewriter to buy groceries, and

then when he had the idea for a story he no longer had the typewriter. He couldn't

get it out of hock because held consumed the groceries and they wouldn't take the

wrappers.

Chat: Were you living in California at the time?

Bloch: No. I went to California for the first time in 1937; I stayed

with Hank Kuttner five weeks. It was at that occasion I met Fritz Leiber, Forry

Ackerman, and C.L. Moore. I fell in love with California; it was a different world,

an ideal place to be. So when 1946 came around with Pacificon, I went out there

again. Tucker and I did meet on the lake, we were in boats, and we

did bump into one another. We switched chicks or something of that sort and

we spent the rest of the weekend together, and from that time on it's been downhill

all the way. I went back again in `47; I didn't move out there until the end of

1959.

Chat: When did you become a professional writer?

Bloch: I was a professional in 1934, I'm afraid to say, but it's true.

I've known this gentleman, and I use the term ill-advisedly, for 32 years. It's

been quite an experience.

Chat: What was your first published story?

Bloch: "The Feast in the Abbey," in Weird Tales, in the January,

1935 issue which actually came out the first of November in 1934. They always

issued them two months in advance in those days.

Tucker: Robert has seniority on me. He sold that story, although it

appeared in the January `35 issue, about June or July in 1934 as I recall.

Magazines have a long lead time. So he became a dirty old pro, underline the word

dirty, in June or July of `34 and he has a terrific seniority on me because I did

not sell my first story until about January of `41, something like that. It was

called...

Bloch: "Slan."

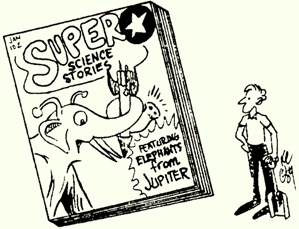

Tucker: (Laughs) "Slan!" I used the pen name A.E. Van Vogt! No, it

was called "Interstellar Way Station." Fred Pohl bought it and published it in

Super Science Novels. So anyway, Bob has seven years seniority on me, and

believe me, on him it shows!

Bloch: (Laughs) I've always wondered about Bob's first story, you know.

I wonder why he didn't quit when he was ahead.

Bloch: (Laughs) I've always wondered about Bob's first story, you know.

I wonder why he didn't quit when he was ahead.

Tucker: (Laughs) Robert and I discovered something at Pacificon; we

discovered that we could have more fun milking an audience by pretending to stab

one another, heckle one another, than we could by playing buddy-buddy. We get up

on stage together and play buddy-buddy and they doze, they nod, they fall asleep.

We heckle one another and they're wide awake and alert awaiting the next sharply

pointed knife.

Chat: Bob, how did you get involved with Hollywood?

Bloch: I got involved with Hollywood when I was about 3 years old, by

going to silent movies. I'll never forget it. There was one silent film where a

train would rush toward the audience and everyone would cower in their seats. I

went under my seat, and when I lifted my head again there was a picture on

with a very funny comedian in it; it was a two-reel comedy with Buster Keaton. And

it took me until 1960 to meet Bus, when I went out to Hollywood and I found myself

on a baseball team with Buster. He was the pitcher and the late Dan Blocker was

the catcher. That was quite a game!

Tucker: What position did you play?

Bloch: I was, um, way out in left field! (Everybody laughs)

From that moment we became fast friends. But the point, if any, was that I became

a movie fan, a real movie buff. And I was very, very enamored of screen work. I

never thought I'd get into it. But finally in 1959, 1 got an opportunity to do a

television show. I went out and did it, and at the same time my novel Psycho

was bought, which was then screened and released in 1960. So I've been involved

more or less ever since.

Chat: What are your thoughts on Psycho? It's made you famous,

if nothing else, but has it made you famous in a way you desire?

Bloch: Believe me, I have nothing but gratitude for all the things

that have happened to me in my life. Look at the wonderful things that science

fiction has done. By picking up a magazine when I was 10 years old, I didn't

realize I was opening the door to a world that was going to give me a whole lifetime

of pleasure and enable me to meet hundreds of people that I would not otherwise have

met. I'm very grateful to all it has given me, in spite of Tucker.

Chat: You won your Hugo in 1959 for the short story, "That Hell-Bound

Train." How many times have you been nominated?

Bloch: That's the only time. You know, I didn't even know I was up

for it. I really didn't know that the story had been nominated. In 1959, I was at

the Detroit Worldcon; Isaac Asimov was the Toastmaster and he asked me to help him

out because, you know, he's pretty inarticulate. (Tucker laughs at this) I was to

hand out the Hugos. I was opening the envelope and I saw my name on the list of

nominations. I didn't even know of it. When the story won, I was flabbergasted.

Chat: Bob, you won your Hugo for Best Fan Writer, I believe. When was

that?

Tucker: The award was granted in 1970 for the year 1969. But do not

accept that at face value. I've been writing for fanzines since my first fanzine

appearance in 1932. When they got around to nominating me in 1969 for the 1970

award, it was for those 30 or 40 years of fan writing rather than the previous year.

They were simply giving me a grandfather award, and it was understood as such.

Chat: Have you felt disappointment never having won for fiction?

Tucker: I've had two books nominated. The first Hugo awards were

given out in 1953 in Philadelphia. They weren't called Hugos then; they were merely

Achievement Awards. My book The Long Loud Silence, published in 1952, was

one of the nominees for that year, but lost to Alfred Bester's The Demolished

Man, which truly deserved to win. In 1970, The Year of the Quiet Sun was

nominated along with Silverberg's Tower of Glass and Niven's Ringworld.

And Ringworld won. My book came in number four of the five finalists. So

I've been nominated twice, and quite honestly, I've been beaten by better books

both times.

Chat: Thinking back over your years as a writer and a fan, can you

think of anything especially significant or noteworthy?

Tucker: Go back to 1943, the first time you were Guest of Honor.

Bloch: Oh, yes, Toronto! I was Guest of Honor at the Worldcon in

Toronto because this character over here made that suggestion. He's the guy who

said "Make him Guest of Honor," so they did. We went up there; things were a little

bit different. There were about 200 people at this affair and they had a small

banquet. We paid for our own banquet tickets; I mean, the Guests of Honor and

Toastmaster paid for their own banquet tickets!

Tucker: No freebies in those days. The cons were too small and too

poor. They couldn't afford to pay for it. At that Worldcon he was Pro Guest of

Honor and I was Fan Guest of Honor. This was the first time we appeared on a

program together. That's how we discovered we could play straight man or jab at

each other.

Bloch: What happened was that Tucker had gotten together a very

elaborate survey on fandom; an anthropological study complete with charts and

diagrams. He'd done considerable serious and intensive research through

correspondence, questionnaire, and documentation. He presented this thing as part

of the formal program. As luck would have it, they had to have something to do at

the banquet; it was a matter of whoever was there would contribute something. So,

I turned up the next day at the banquet, and I, too, had a survey of fandom with

some charts which I had done in my room the previous night. It was a deliberate

contradiction of Tucker's findings.

Tucker: (Laughing) Bloch did the most beautiful job imaginable. Now,

picture me with this solidly researched and backgrounded survey; I actually sent out

hundreds of questionnaires, and my charts were accurate as of that day. Imagine

Bloch getting up there with his fake charts and very neatly in a few words, a few

quick slits of that knife, he cut the ground from under me and I fell through the

stage. He sabotaged me wonderfully well.

Bloch: What was the situation when you laid down on the streetcar

tracks?

Tucker: Ah! In 1948, the United States was abandoning streetcars in

favor of buses. Canada, being more enlightened, kept their trains and trolley cars.

And Toronto, on a Sunday in 1948, was the deadest thing next to Jacksonville,

Illinois in 1978. I live in Jacksonville.

{{ ed. note: at that

time, anyway}} In Jacksonville now, during the week the good citizens go out

in their backyards, sit on the patio and watch the grass grow. That's excitement!

On that Saturday night in Toronto in 1948, the whole con goes down to the

intersection and watches the red light blink. So the next day, Sunday, we left the

hotel and went to the restaurant and it was closed, we got to the bar and it was

closed; the only thing to do was go down the street to where the convention was in

the process of closing. And it happened that we had to cross the street where there

was tramway tracks in the middle. We looked up and down the street and there wasn't

a damn thing to be seen, so to show these backward Canadians how forward-looking we

Americans were, I laid down on the streetcar tracks and dared one to run over

me! And nothing happened! All the streetcars were in the garage! ed. note: at that

time, anyway}} In Jacksonville now, during the week the good citizens go out

in their backyards, sit on the patio and watch the grass grow. That's excitement!

On that Saturday night in Toronto in 1948, the whole con goes down to the

intersection and watches the red light blink. So the next day, Sunday, we left the

hotel and went to the restaurant and it was closed, we got to the bar and it was

closed; the only thing to do was go down the street to where the convention was in

the process of closing. And it happened that we had to cross the street where there

was tramway tracks in the middle. We looked up and down the street and there wasn't

a damn thing to be seen, so to show these backward Canadians how forward-looking we

Americans were, I laid down on the streetcar tracks and dared one to run over

me! And nothing happened! All the streetcars were in the garage!

Bloch: But there was a streetcar on Sunday. That morning I

took one to a park to see the elephants. I'm very big on elephants.

Bloch: But there was a streetcar on Sunday. That morning I

took one to a park to see the elephants. I'm very big on elephants.

Tucker: Well, Robert has always followed the elephants. Usually with

a shovel. (And everybody laughs)

Chat: You two are amazing. Have either of you any last comments? Or

rebuttals?

Bloch: I'm so glad you did this on Friday night while we're still

alive.

Tucker: And reasonably sober.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

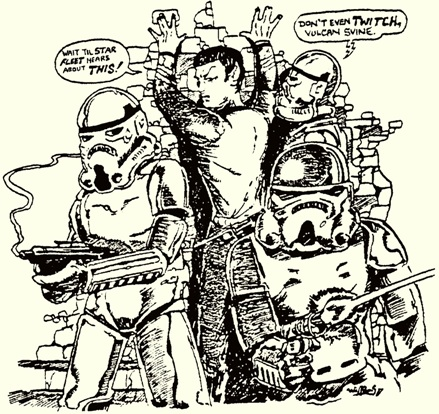

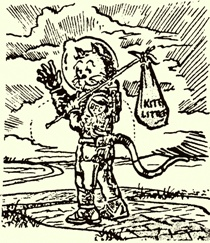

That first year of Chat also

produced another friendship that's lasted to this day, although we rarely see much of

him anymore. In Chat 8 (May 1978) we were the first fanzine to publish

work by fanartist Charlie Williams. We were introduced to Chuckles through a mutual

friend; at the time he was co-owner of small comics store in Knoxville and teaching

a University of Tennessee extension course in cartoon illustration. Dick's intro of

him in Chat read: That first year of Chat also

produced another friendship that's lasted to this day, although we rarely see much of

him anymore. In Chat 8 (May 1978) we were the first fanzine to publish

work by fanartist Charlie Williams. We were introduced to Chuckles through a mutual

friend; at the time he was co-owner of small comics store in Knoxville and teaching

a University of Tennessee extension course in cartoon illustration. Dick's intro of

him in Chat read:

"In my opinion, Charlie is a damn fine illustrator, good enough to win some day

(soon!) the fan artist Hugo. Remember you saw his work here first!"

Well, it's turned out that Charlie has

never been ultra-active enough to garner enough interest for a nomination, but he has

over the years gained notice. Mike Glyer once even listed him in File 770 as

one of the five best fan artists of the year. From his slick style and sharp wit,

it's easy to see why... Well, it's turned out that Charlie has

never been ultra-active enough to garner enough interest for a nomination, but he has

over the years gained notice. Mike Glyer once even listed him in File 770 as

one of the five best fan artists of the year. From his slick style and sharp wit,

it's easy to see why...

Charlie Williams was the bridge that

took us from year one to year two of Chat. We had gone to our first Worldcon

(IguanaCon in Phoenix) that August, and had brought a few issues with us for trade or

giveaway. While in Phoenix, we went to a program item on fan publishing and met Brian

Earl Brown, who was just starting his fanzine reviewzine, Whole Fanzine Catalog,

about then. Not too long after, we started getting favorable reviews from Brian, and

one of the things he often mentioned (and what undoubtedly caught his eye in the first

place) was the Williams artwork. And soon after that, tradezines started appearing

with regularity, and letters of comment on any particular issue started becoming

commonplace instead of unusual. It was clear that we'd reached "critical mass". Charlie Williams was the bridge that

took us from year one to year two of Chat. We had gone to our first Worldcon

(IguanaCon in Phoenix) that August, and had brought a few issues with us for trade or

giveaway. While in Phoenix, we went to a program item on fan publishing and met Brian

Earl Brown, who was just starting his fanzine reviewzine, Whole Fanzine Catalog,

about then. Not too long after, we started getting favorable reviews from Brian, and

one of the things he often mentioned (and what undoubtedly caught his eye in the first

place) was the Williams artwork. And soon after that, tradezines started appearing

with regularity, and letters of comment on any particular issue started becoming

commonplace instead of unusual. It was clear that we'd reached "critical mass".

New contributors started showing up that

second year, too. SFWA members Sharon Webb, Ralph Roberts, and Perry Chapdelaine all

provided material for publication; Chapdelaine's was a free-wheeling, opinionated monthly

column on writing, small press publishing, and related things. About then, we also

started getting noticed by other fanartists. Cartoons and spot illos by local area

fanartists Cliff Biggers, Roger Caldwell, Jerry Collins, Rusty Burke, and Wade Gilbreath

started adding variety to each issue, and we even received contributions from some

well-known out-of-region fanartists, like Jeanne Gomoll, Victoria Poyser, and Alexis

Gilliland. The 18th issue (March 1979) had a full-page cover by Gilbreath; previous to New contributors started showing up that

second year, too. SFWA members Sharon Webb, Ralph Roberts, and Perry Chapdelaine all

provided material for publication; Chapdelaine's was a free-wheeling, opinionated monthly

column on writing, small press publishing, and related things. About then, we also

started getting noticed by other fanartists. Cartoons and spot illos by local area

fanartists Cliff Biggers, Roger Caldwell, Jerry Collins, Rusty Burke, and Wade Gilbreath

started adding variety to each issue, and we even received contributions from some

well-known out-of-region fanartists, like Jeanne Gomoll, Victoria Poyser, and Alexis

Gilliland. The 18th issue (March 1979) had a full-page cover by Gilbreath; previous to

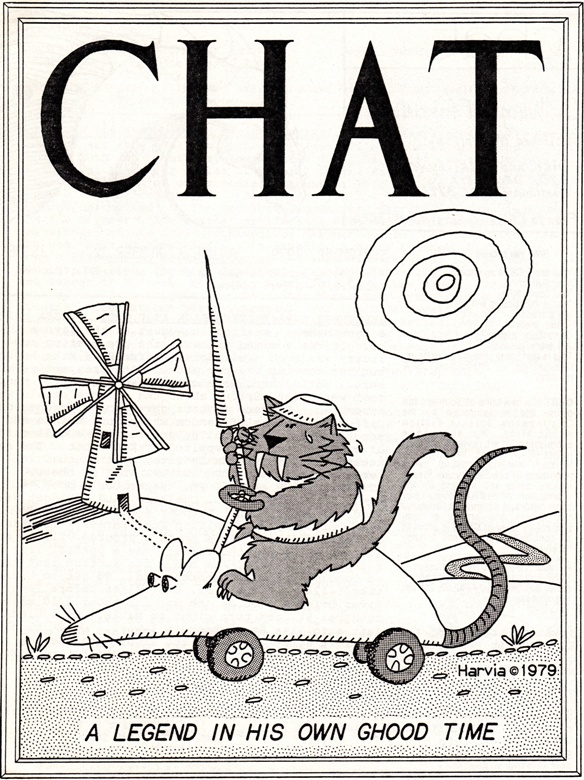

that, we had just run a logo and colophon at the top of page one and jumped right into

local fan news. The club members seemed to like it, and we never did publish another

issue without full page cover art. Succeeding months featured covers by Williams, Taral

Wayne, and Kurt Erichsen, as well as by local fanartists Julie Scott, Tom Walker, Bob

Barger, Earl Cagle, and Rusty Burke. One other fanartist who responded to a request for

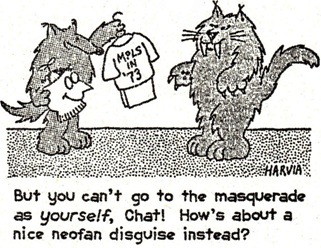

artwork was Teddy Harvia, and his cartoon, that appeared in the 21st issue (June 1979)

introduced the saber-toothed tiger mascot that became identified with Chat during

the second half of its run.

that, we had just run a logo and colophon at the top of page one and jumped right into

local fan news. The club members seemed to like it, and we never did publish another

issue without full page cover art. Succeeding months featured covers by Williams, Taral

Wayne, and Kurt Erichsen, as well as by local fanartists Julie Scott, Tom Walker, Bob

Barger, Earl Cagle, and Rusty Burke. One other fanartist who responded to a request for

artwork was Teddy Harvia, and his cartoon, that appeared in the 21st issue (June 1979)

introduced the saber-toothed tiger mascot that became identified with Chat during

the second half of its run.

Cat cartoons were a common theme in

Chat after that. Letters of Comment or their envelopes often had some kind of cat

sticker or stamp. We even received a coffee cup in the mail from the Barnard-Columbia

University SF Club (in lieu of a LoC, presumably) that depicted a contented-looking cat

and the words "Le Chat". Harvia followed up his Chat cartoon in that same issue with an

amusing commentary about how he came to draw it; here it is again... Cat cartoons were a common theme in

Chat after that. Letters of Comment or their envelopes often had some kind of cat

sticker or stamp. We even received a coffee cup in the mail from the Barnard-Columbia

University SF Club (in lieu of a LoC, presumably) that depicted a contented-looking cat

and the words "Le Chat". Harvia followed up his Chat cartoon in that same issue with an

amusing commentary about how he came to draw it; here it is again...

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

"A True Story"

Teddy Harvia

"A True Story"

Teddy Harvia

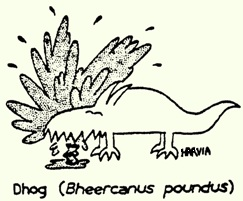

Saturday last, dhog brought me the mail.

I hadn't even heard the postman at the box. I tossed dhog a bheer and he preceeded to

pound on the tab with his teeth. Saturday last, dhog brought me the mail.

I hadn't even heard the postman at the box. I tossed dhog a bheer and he preceeded to

pound on the tab with his teeth.

A "Mpls in 73" flyer, a love letter from

my girlfriend in France, and a fanzine from Chattanooga -- not much, I thought, as I

glanced through the mail. But the last had me wondering. I don't know anyone in

Chattanooga except McPherson Strutts, and he doesn't count. A "Mpls in 73" flyer, a love letter from

my girlfriend in France, and a fanzine from Chattanooga -- not much, I thought, as I

glanced through the mail. But the last had me wondering. I don't know anyone in

Chattanooga except McPherson Strutts, and he doesn't count.

A hand-marked block on the inside page

explained why I had received the fanzine. Its editors wanted art. No problem, I

decided. A hand-marked block on the inside page

explained why I had received the fanzine. Its editors wanted art. No problem, I

decided.

Suddenly, a shower of bheer suds

descended on my head. Dhog had opened his bheer. I glared at him as he happily tried

to catch the jet shootlng from the can. You'll have to clean up this mess, I told him,

but knew that he wouldn't. He never did. A creature as independent as dhog, who

insists on opening his own bheers, has no master. Suddenly, a shower of bheer suds

descended on my head. Dhog had opened his bheer. I glared at him as he happily tried

to catch the jet shootlng from the can. You'll have to clean up this mess, I told him,

but knew that he wouldn't. He never did. A creature as independent as dhog, who

insists on opening his own bheers, has no master.

I set the fanzine aside to dry. I set the fanzine aside to dry.

Later that day I relaxed with dhog on my

feet to read Chat through the bheer stains and teeth marks. Words and comments

here and there brought cartoon ideas to mind, but I dismissed them one by one. All in

Chat seemed temporal, unlikely to recur in the next issue. I needed a cartoon

idea which was outside time. Later that day I relaxed with dhog on my

feet to read Chat through the bheer stains and teeth marks. Words and comments

here and there brought cartoon ideas to mind, but I dismissed them one by one. All in

Chat seemed temporal, unlikely to recur in the next issue. I needed a cartoon

idea which was outside time.

Why not just send a cartoon from your

file, dhog suggested. They would know, I responded. They would think I hadn't even

taken the time to read their fanzine. Why not just send a cartoon from your

file, dhog suggested. They would know, I responded. They would think I hadn't even

taken the time to read their fanzine.

For two hours I read and reread the

issue. I went line by line, word by word, until my mind and body finally fell exhausted

into a fitful sleep. For two hours I read and reread the

issue. I went line by line, word by word, until my mind and body finally fell exhausted

into a fitful sleep.

In a dream, the 'h' in the title of the

fanzine faded away. It was so obvious, I suddenly realized, that the stuff of fannish

legends had been staring me in the face all the time. In a dream, the 'h' in the title of the

fanzine faded away. It was so obvious, I suddenly realized, that the stuff of fannish

legends had been staring me in the face all the time.

I leapt awake, rolling dhog off my feet

and across the floor. The idea became a scrawled note. Dhog mumbled for another

bheer. I leapt awake, rolling dhog off my feet

and across the floor. The idea became a scrawled note. Dhog mumbled for another

bheer.

The next day, with only slight changes,

I inked the caption. But the accompanying sketch seemed inadequate. Dhog yawned with

disinterest at the cat I had drawn. The next day, with only slight changes,

I inked the caption. But the accompanying sketch seemed inadequate. Dhog yawned with

disinterest at the cat I had drawn.

The sketch lay for three days on my desk.

The gulf between conception and execution seemed infinitely wide. I knew eventually I

would send off the cartoon, whatever its final form. But I hesitated. The legend

seemed to demand time. The sketch lay for three days on my desk.

The gulf between conception and execution seemed infinitely wide. I knew eventually I

would send off the cartoon, whatever its final form. But I hesitated. The legend

seemed to demand time.

Tuesday afternoon a vision from my past

entered my mind. I remembered as a child wondering at the drawing of a saber-toothed

tiger in the encyclopedia. Suddenly the beast was before me. His scream lifted the

hair on the back of my neck. I was face-to-face with primal fantasy. Tuesday afternoon a vision from my past

entered my mind. I remembered as a child wondering at the drawing of a saber-toothed

tiger in the encyclopedia. Suddenly the beast was before me. His scream lifted the

hair on the back of my neck. I was face-to-face with primal fantasy.

As quickly as it had appeared, it

vanished back into prehistory. I hurriedly tried to sketch its essence. As quickly as it had appeared, it

vanished back into prehistory. I hurriedly tried to sketch its essence.

At home that night I faithfully traced

the creature in ink. When I showed the finished drawing to dhog, his ears shot straight

up in the air. And I knew I had captured the legend on paper. At home that night I faithfully traced

the creature in ink. When I showed the finished drawing to dhog, his ears shot straight

up in the air. And I knew I had captured the legend on paper.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

It turned out that Teddy Harvia's "Fourth

Fannish Ghod" article generated more fan mail than anything else that ever appeared in

Chat. But what was more interesting was that it seemed to be the catalyst for a

larger number of LoCs. Where we were hard pressed to find two or three pages of letters

to print, every issue after that we didn't have any problem filling five or more pages,

even with the tiny reduced print and narrow margins we were using to keep the pagecount

to a manageable number. The most amusing response to the "Chat" article was from Sharon

Webb, who wrote: It turned out that Teddy Harvia's "Fourth

Fannish Ghod" article generated more fan mail than anything else that ever appeared in

Chat. But what was more interesting was that it seemed to be the catalyst for a

larger number of LoCs. Where we were hard pressed to find two or three pages of letters

to print, every issue after that we didn't have any problem filling five or more pages,

even with the tiny reduced print and narrow margins we were using to keep the pagecount

to a manageable number. The most amusing response to the "Chat" article was from Sharon

Webb, who wrote:

"Loved Harvia's fourth fannish ghod, Chat. I was so impressed that I was driven to

do some research on the subject: The ghod is, of course, a chatamount. His favorite

food is chatfish, but chatbird is violently poisonous to him. Upon ingestion of chatbird

the chat will exhibit the chatastrophic symptoms of chataplexy. If the remedy (Chatalpha

Chaterpillar) is withheld, the chondition rapidly progresses to a state of chatalepsy.

"I would hope that the fourth fannish ghod Chat sees fit to reveal himself to us at

Chattacon 5."

"I would hope that the fourth fannish ghod Chat sees fit to reveal himself to us at

Chattacon 5."

Unfortunately, it was not to be. While

Chattacon 5 (January 1980) indeed had a masquerade, nobody entered as "Chat". Back

then, convention masquerading had not become the relatively big-time craft it is now, and

apparently nobody who read Chat was very much into that aspect of fandom. A "Chat"

costume would have been amusing. Unfortunately, it was not to be. While

Chattacon 5 (January 1980) indeed had a masquerade, nobody entered as "Chat". Back

then, convention masquerading had not become the relatively big-time craft it is now, and

apparently nobody who read Chat was very much into that aspect of fandom. A "Chat"

costume would have been amusing.

By the time Chattacon 5 rolled around,

most of the "Chat" puns had run their course; by then everyone in the club was thinking

more about the upcoming convention than of mythical saber-toothed tigers. After more than

two years, the club itself had grown quite a bit from its modest beginnings. No longer

were meetings held at the home of one of the members; it wasn't unusual to have 25 or more By the time Chattacon 5 rolled around,

most of the "Chat" puns had run their course; by then everyone in the club was thinking

more about the upcoming convention than of mythical saber-toothed tigers. After more than

two years, the club itself had grown quite a bit from its modest beginnings. No longer

were meetings held at the home of one of the members; it wasn't unusual to have 25 or more

people at a meeting by then, and the club treasury had grown to *gasp* over a hundred

dollars (those were big numbers back then for a small metro area like Chattanooga). It

didn't go unnoticed by a certain few club members that even though the club was

contributing less than half of the publishing costs, Chat was still siphoning off

what was considered a significant share (usually between $5 and $15 a month) of club dues

that could have gone into more down-to-earth endeavors, like throwing a big

treasury-depleting party each month. And smaller, less costly issues of Chat would

mean more money for bigger and better parties yet. Personality differences within the

club were starting to build that would affect the club as a whole and Chat in

particular, even if we weren't fully aware of it at the time. We certainly wouldn't have

believed it then if somebody had told us that we would cease publication after just one

more year.

people at a meeting by then, and the club treasury had grown to *gasp* over a hundred

dollars (those were big numbers back then for a small metro area like Chattanooga). It

didn't go unnoticed by a certain few club members that even though the club was

contributing less than half of the publishing costs, Chat was still siphoning off

what was considered a significant share (usually between $5 and $15 a month) of club dues

that could have gone into more down-to-earth endeavors, like throwing a big

treasury-depleting party each month. And smaller, less costly issues of Chat would

mean more money for bigger and better parties yet. Personality differences within the

club were starting to build that would affect the club as a whole and Chat in

particular, even if we weren't fully aware of it at the time. We certainly wouldn't have

believed it then if somebody had told us that we would cease publication after just one

more year.

For that and other reasons, the

Chattacon 5 issue of Chat, number 28 (January 1980), was another transitional

issue. Gone was the photocopier method of repro; Dick had felt more and more uncomfortable

about using his employer's Xerox machine to run off higher and higher copy counts of greater

and greater pagecounts each month. It had become unmanageable, so we had acquired an

honest-to-goodness Gestetner mimeo and electrostencil machine for future fanzine projects.

Chat 28 was the first of them. For that and other reasons, the

Chattacon 5 issue of Chat, number 28 (January 1980), was another transitional

issue. Gone was the photocopier method of repro; Dick had felt more and more uncomfortable

about using his employer's Xerox machine to run off higher and higher copy counts of greater

and greater pagecounts each month. It had become unmanageable, so we had acquired an

honest-to-goodness Gestetner mimeo and electrostencil machine for future fanzine projects.

Chat 28 was the first of them.

That issue was also memorable from the

article by Bob Tucker in it. Every January since our first meeting with him in Arkansas,

he'd been a guest at Chattacon, and had spent a few days with us before or after the

convention. His visit in early 1980 was particularly memorable, because he drove down

with Lou Tabakow from Cincinnati; Lou was already in the early stages of Lou Gehrig's

Disease that would eventually claim him, but we remember the two days they spent with us

before the convention were two of the most fun days we've ever had. Bob was Toastmaster

of that Chattacon and was the subject of "The Last Whole Earth Bob Tucker Roast" at the

Saturday night banquet, a truly funny and entertaining event of which sadly no

documentation remains. He had also contributed an amusing article of fan history interest

that was printed in the Program Book and also in Chat. Here it is again... That issue was also memorable from the

article by Bob Tucker in it. Every January since our first meeting with him in Arkansas,

he'd been a guest at Chattacon, and had spent a few days with us before or after the

convention. His visit in early 1980 was particularly memorable, because he drove down

with Lou Tabakow from Cincinnati; Lou was already in the early stages of Lou Gehrig's

Disease that would eventually claim him, but we remember the two days they spent with us

before the convention were two of the most fun days we've ever had. Bob was Toastmaster

of that Chattacon and was the subject of "The Last Whole Earth Bob Tucker Roast" at the

Saturday night banquet, a truly funny and entertaining event of which sadly no

documentation remains. He had also contributed an amusing article of fan history interest

that was printed in the Program Book and also in Chat. Here it is again...

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

A Scholarly Report on an Almost-Lost Art Form

Bob Tucker

A Scholarly Report on an Almost-Lost Art Form

Bob Tucker

"Lez-ettes" was the name given to the

very-short stories which appeared between 1940 and 1968 in a fanzine called Le Zombie.

That was a time when fandom was very young and had not yet gained a social conscience, and

refused to take itself seriously. "Lez-ettes" was the name given to the

very-short stories which appeared between 1940 and 1968 in a fanzine called Le Zombie.

That was a time when fandom was very young and had not yet gained a social conscience, and

refused to take itself seriously.

The appeal of the stories was that they each

consisted of only three chapters, and each chapter contained but one word. (A very few

stories contained more than one word per chapter, but they were not as popular and as pithy

as the single-word chapters.) The appeal of the stories was that they each

consisted of only three chapters, and each chapter contained but one word. (A very few

stories contained more than one word per chapter, but they were not as popular and as pithy

as the single-word chapters.)

Two examples follow: Two examples follow:

Chapter One:

Fan

Chapter Two:

Fanne

Chapter Three:

One-Shot

|

Chapter One:

Jill

Chapter Two:

Pill

Chapter Three:

Nil

|

The Lez-ettes were the invention of the old

Slan Shack gang in Battle Creek, Michigan, and were written by Walt Liebscher, Al Ashley,

Jack Wiedenbeck, E.E. Evans, and myself. The rules for writing them were simple: each

chapter was to contain only one word, if possible, and the three chapters taken together

should tell a coherent story, with the third and last chapter being reserved for the climax

or culmination. The kind of story a Big Name Editor was likely to buy if he wasn't afraid

of being fired. The Lez-ettes were the invention of the old

Slan Shack gang in Battle Creek, Michigan, and were written by Walt Liebscher, Al Ashley,

Jack Wiedenbeck, E.E. Evans, and myself. The rules for writing them were simple: each

chapter was to contain only one word, if possible, and the three chapters taken together

should tell a coherent story, with the third and last chapter being reserved for the climax

or culmination. The kind of story a Big Name Editor was likely to buy if he wasn't afraid

of being fired.

The chapters were to be set out as

illustrated in this report, and the desired goal was to be as terse and as clever as

possible but to always tell a complete story. The chapters were to be set out as

illustrated in this report, and the desired goal was to be as terse and as clever as

possible but to always tell a complete story.

That which follows is a reprinting of the

"better" stories taken from the pages of Le Zombie during the years mentioned above,

and you are invited to contribute to the art form and so prevent it from becoming entirely

lost. Try your fine hand at this exciting kind of fiction. You may win fame and fortune,

but, unfortunately, you won't become eligible for membership in the Science Fiction Writers

of America. That which follows is a reprinting of the

"better" stories taken from the pages of Le Zombie during the years mentioned above,

and you are invited to contribute to the art form and so prevent it from becoming entirely

lost. Try your fine hand at this exciting kind of fiction. You may win fame and fortune,

but, unfortunately, you won't become eligible for membership in the Science Fiction Writers

of America.

|

|

Chapter One:

Prison

Chapter Two:

Nitrous Oxide

Chapter Three:

Silicon

|

Chapter One:

Sun

Chapter Two:

None

Chapter Three:

All Done

|

|

|

|

Chapter One:

Constellation

Chapter Two:

Constipation

Chapter Three:

Nova

|

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

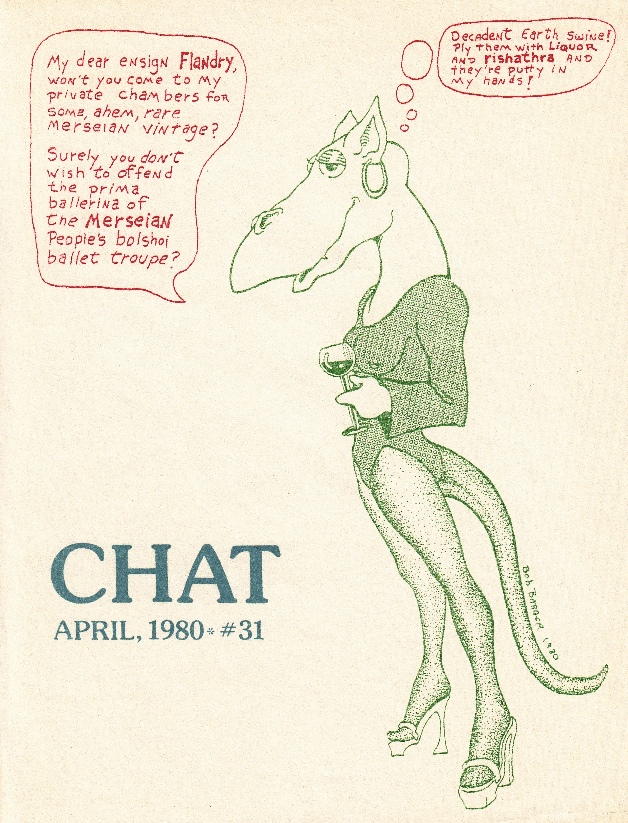

Switching over to mimeo had an additional

side benefit -- it allowed us to use color in Chat. Issue 31 (April 1980) was the

first one where we used different colored mimeo inks; it had a three-color cover by local

fanartist Bob Barger. There wasn't as much reader response as we thought there would be, Switching over to mimeo had an additional

side benefit -- it allowed us to use color in Chat. Issue 31 (April 1980) was the

first one where we used different colored mimeo inks; it had a three-color cover by local

fanartist Bob Barger. There wasn't as much reader response as we thought there would be,

although it did catch the attention of Taral, who was doing fanzine reviews for Mike

Glyer's File 770 at the time. Taral gave Chat a somewhat

positive review -- he praised it for use of color mimeo and appearance, but thought we

were pretty well hemmed-in by the clubzine format and monthly deadlines. He suggested

we might be better off doing a different kind of fanzine.

although it did catch the attention of Taral, who was doing fanzine reviews for Mike

Glyer's File 770 at the time. Taral gave Chat a somewhat

positive review -- he praised it for use of color mimeo and appearance, but thought we

were pretty well hemmed-in by the clubzine format and monthly deadlines. He suggested

we might be better off doing a different kind of fanzine.

We were starting to think along those same

lines ourselves, but frankly, we liked publishing Chat and the growing number

of fannish contacts we were making because of it -- it wasn't unusual to find letters from

Canada, England, Australia, Italy, or even Minnesota in our mailbox. Besides, after three

years, that little saber-toothed tiger was part of the family. So we pressed on. We were starting to think along those same

lines ourselves, but frankly, we liked publishing Chat and the growing number

of fannish contacts we were making because of it -- it wasn't unusual to find letters from

Canada, England, Australia, Italy, or even Minnesota in our mailbox. Besides, after three

years, that little saber-toothed tiger was part of the family. So we pressed on.

There were other color covers after that.

For very next issue, Chat 32 (May 1980), we managed to work in all four

mimeo ink colors we had; fortunately it was a fairly simple cover with lots of white space

as buffer between colors. And there were three issues after that, 34 through 38, that had

two-color covers. However, we soon discovered to our dismay that although we now had the

means to do multi-color mimeo, we still didn't necessarily have the time. Deadlines fell

just too close together. And it added somewhat to the cost of the fanzine, which again was

starting to be an issue with the club. There were other color covers after that.

For very next issue, Chat 32 (May 1980), we managed to work in all four

mimeo ink colors we had; fortunately it was a fairly simple cover with lots of white space

as buffer between colors. And there were three issues after that, 34 through 38, that had

two-color covers. However, we soon discovered to our dismay that although we now had the

means to do multi-color mimeo, we still didn't necessarily have the time. Deadlines fell

just too close together. And it added somewhat to the cost of the fanzine, which again was

starting to be an issue with the club.

By the time that the third annish,

Chat 37 (October 1980) came out, growing personality differences had polarized

the club to the point where it was in effect two different and competing fan organizations.

There wasn't any semblance of unity anymore, and meetings had started to become

confrontational to the point where we no longer looked forward each month to attending.

It was obvious that sorneone needed to stir things up a bit, to at least try to

regain some semblance of unity. So, in issue 37, someone did. By the time that the third annish,

Chat 37 (October 1980) came out, growing personality differences had polarized

the club to the point where it was in effect two different and competing fan organizations.

There wasn't any semblance of unity anymore, and meetings had started to become

confrontational to the point where we no longer looked forward each month to attending.

It was obvious that sorneone needed to stir things up a bit, to at least try to

regain some semblance of unity. So, in issue 37, someone did.

The article was titled "A Statement of

Intent," and was written by a club member known for his sharp sense of humor.

We ran it as an editorial, although in retrospect it might have been betten as a letter of

comment. In any event, it succeeded in stirring things up, but probably not in the way

that was intended. Here is the text: The article was titled "A Statement of

Intent," and was written by a club member known for his sharp sense of humor.

We ran it as an editorial, although in retrospect it might have been betten as a letter of

comment. In any event, it succeeded in stirring things up, but probably not in the way

that was intended. Here is the text:

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

"Some time ago at a meeting-after-the-meeting

meeting, it was noted that the Chattanooga fandom had lost sight of itself. That is, that

it is no longer concerned with science fiction and SF fandom, and that it had become

chaotic, directionless, and was turning into a party club. Let's face it; any bunch of

half-drunk mundane idiots can get together and have a party. SF fandom is supposed to be

better than the mundane world, not just like it.

"So it was decided that CSFA needed a leader, one who would provide a structure of

continuity both within the meeting and from meeting so meeting, not just someone who just

stands in front of everybody and lets everybody talk at once. The SMOFs conferred on this

leader (as yet nameless) as unlimited an authority over meetings as his henchmen could

secure for him. However, there seemed to be no one to entrust this power to due to either

lack of time or fear of lack of experience in wielding power. No one that is, but

myself.

"I did not want this position but I recognized that another candidate might not have my

determination for reform and improvement for CSFA. The SMOFs understood this and assented

to the inevitable.

"Therefore, at the October meeting there will be a short ceremony of investation wherein I

will assume power and appoint my henchmen. Afterwards the meeting will begin along

guidelines set forth by me.

"Wishing myself well and the CSFA renewed health and prosperity, this is your friend and

servant..."

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Unfortunately, the message that was presented,

namely the obviousness that the club needed some revitalization, was misinterpreted as an

attempt to wrest control of the club. The fact that there was never any control to wrest,

the club having been organized as essentially an anarchy, wasn't considered. An uproar

ensued, with all kinds of accusations being tossed about, and what happened was that

Chat itself became the focus of all the unpleasantness that was going on. The next

three issues had a lively debate in the letters column about what does or doesn't make for

an interesting meeting, and we were both surprised and pleased to get correspondence from

readers in other cities comparing similar situations in their local clubs with CSFA. The

most interesting and gratifying was from a fan in Philadelphia, who wrote: Unfortunately, the message that was presented,

namely the obviousness that the club needed some revitalization, was misinterpreted as an

attempt to wrest control of the club. The fact that there was never any control to wrest,

the club having been organized as essentially an anarchy, wasn't considered. An uproar

ensued, with all kinds of accusations being tossed about, and what happened was that

Chat itself became the focus of all the unpleasantness that was going on. The next

three issues had a lively debate in the letters column about what does or doesn't make for

an interesting meeting, and we were both surprised and pleased to get correspondence from

readers in other cities comparing similar situations in their local clubs with CSFA. The

most interesting and gratifying was from a fan in Philadelphia, who wrote:

"It is interesting to note the comments about a 'power struggle' and factionalizing

within your club.

"This has heen a problem which has plagued the Philadalphia Science Fiction Society for the

last eight years (since I've been in). The people who do the work are inevitably accused of

trying to grab power. What most people don't realize is there is really almost no power to

be obtained by running the typical regional SF club. And the positions of responsibility

are generally available for those who are interested and dedicated enough to use them.

Unfortunately, there are those who aren't willing to take that approach, and instead seek

titles for their own sakes. This leads to the downfall of the club, as the workers get

disgusted with all the drones. This series of events has occurred countless times in PSFS

and other clubs."

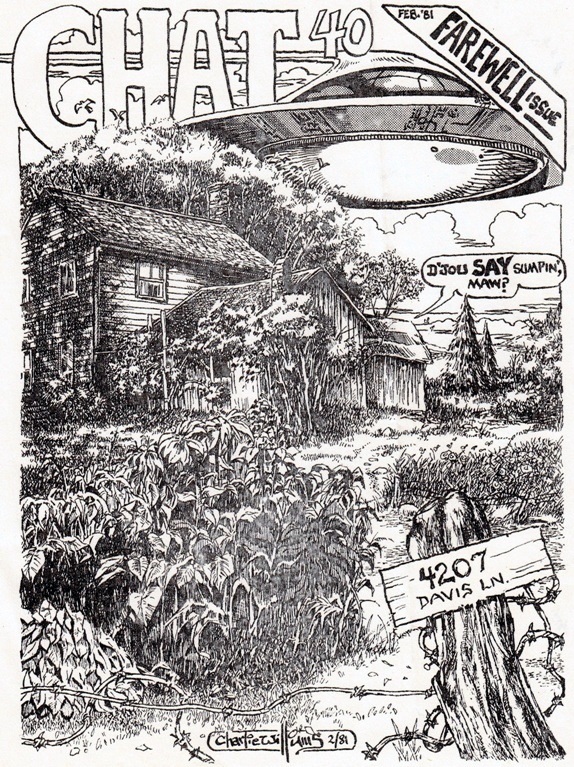

That letter appeared in Chat 40

(February 1981), which was the final issue. By early 1981 we had decided that Taral had

been right after all; we were pretty well hemmed-in by the clubzine format and monthly

deadlines, and had taken Chat about as far as we thought a clubzine could or should be

taken. Twenty pages a month may not sound like much in these days of powerful personal

computers and slick word processing software, but back then each page had to be laboriously

pasted-up from hand-typed copy. We also had decided that things with the club were probably

not going to get better any time soon (they didn't), and we were tiring of all the bullshit.

We longed to do a zine that didn't have or need any affiliations or sources of co-funding.

It was time to try something else -- a different kind of fanzine with a more open publishing

schedule. And so Mimosa was born, the name indicative of our southern fan background,

but like ourselves, not necessarily or even originally from the south. That letter appeared in Chat 40

(February 1981), which was the final issue. By early 1981 we had decided that Taral had

been right after all; we were pretty well hemmed-in by the clubzine format and monthly

deadlines, and had taken Chat about as far as we thought a clubzine could or should be

taken. Twenty pages a month may not sound like much in these days of powerful personal

computers and slick word processing software, but back then each page had to be laboriously

pasted-up from hand-typed copy. We also had decided that things with the club were probably

not going to get better any time soon (they didn't), and we were tiring of all the bullshit.

We longed to do a zine that didn't have or need any affiliations or sources of co-funding.

It was time to try something else -- a different kind of fanzine with a more open publishing

schedule. And so Mimosa was born, the name indicative of our southern fan background,

but like ourselves, not necessarily or even originally from the south.

It's been almost nine years now since the

demise of Chat. In that time, CSFA split into two separate clubs. The original CSFA

hung on for another couple of years before atrophying away; the rival club still exists, It's been almost nine years now since the

demise of Chat. In that time, CSFA split into two separate clubs. The original CSFA

hung on for another couple of years before atrophying away; the rival club still exists,

although it has undergone so many changes in its cast of characters that the differences that

originally led to its formation are probably only dimly if at all remembered. There were other

Chattanooga clubzines after Chat; however, none of them persisted as long, appeared as

regularly, or had as wide a circulation or as varied and interesting a content. Chat

was a product of that rarest of times in any new fan organization, the first few years when

feuds hadn't yet had time to develop.

although it has undergone so many changes in its cast of characters that the differences that

originally led to its formation are probably only dimly if at all remembered. There were other

Chattanooga clubzines after Chat; however, none of them persisted as long, appeared as

regularly, or had as wide a circulation or as varied and interesting a content. Chat

was a product of that rarest of times in any new fan organization, the first few years when

feuds hadn't yet had time to develop.

And we admit there were times during the

early and mid 1980s when we vaguely, but not really seriously, considered resuming publication

in a more newszine-type format. We remember one of those times well; it was a breezy

Tennessee autumn night with the wind singing through the branches of the big Sweet Gum tree

in our backyard. We thought it sounded kind of like a big cat yowling... And we admit there were times during the

early and mid 1980s when we vaguely, but not really seriously, considered resuming publication

in a more newszine-type format. We remember one of those times well; it was a breezy

Tennessee autumn night with the wind singing through the branches of the big Sweet Gum tree

in our backyard. We thought it sounded kind of like a big cat yowling...

Illustrations by Kurt Erichsen, Charlie Williams, and Teddy

Harvia.

Chat 21 cover by Earl Cagle.

Chat 24 cover by Teddy Harvia.

Chat 32 cover by Bob Barger.

Chat 40 cover by Charlie Williams.

|