Well, a year in transition is

about over for us. Last issue, you may recall, was kind of a "Welcome to

Maryland" issue, while the one before that had a "Farewell to Tennessee" theme.

We're not sure what if any theme this issue will have yet (we pretty

much make things up as we go along). Since we've already mentioned being in

transition and given that we're about to transition from the 1980s into the

1990s, here's a remembrance of a different sort of transition, from fan to

pro, from 45 years ago. Well, a year in transition is

about over for us. Last issue, you may recall, was kind of a "Welcome to

Maryland" issue, while the one before that had a "Farewell to Tennessee" theme.

We're not sure what if any theme this issue will have yet (we pretty

much make things up as we go along). Since we've already mentioned being in

transition and given that we're about to transition from the 1980s into the

1990s, here's a remembrance of a different sort of transition, from fan to

pro, from 45 years ago.

- - - - - - - -

A Hugo Gernsback Author

by Dave Kyle

by Dave Kyle

Fantastic stories were a part of my

childhood, a common enough situation for most children. As I evolved into my early

youth, however, I found fairy tales to read which had been modernized into fascinating

stories of the future. In the movies, adult fantasy tales were becoming updated into

horror, with scientific mumbo jumbo. Fantastic stories were a part of my

childhood, a common enough situation for most children. As I evolved into my early

youth, however, I found fairy tales to read which had been modernized into fascinating

stories of the future. In the movies, adult fantasy tales were becoming updated into

horror, with scientific mumbo jumbo.

When I was eleven and twelve years old,

I had not yet discovered that science fiction was a very special genre of fiction with

a very serious aspect. Tom Swift and John Carter and Lord Greystroke represented for

the Wells-Verne imagination in popular, contemporary print. As I approached my teens,

I was verbally spinning horror stories to my chums in the Kyle's back yard orchard, as

inspired by Dracula (1930), Frankenstein (1931), Dr. Jekyll and Mr.

Hyde (1931), Dr. X (1932), etcetera. By age thirteen, however, fairy tales

for me were growing more and more real. I was slipping into the universe of science

fiction. Here were stories more fascinating and intellectually more provocative than I

had previously imagined. I didn't know, at the time, what this kind of literature was

called. There were many identifications, such as Wells' "scientific romances",

Verne's "extraordinary voyages", Appleton's simple yarns of young inventor Tom Swift,

Burroughs' swashbuckling adventures in other worlds that were in, on and off Earth,

and a host of descriptions with worlds like "unusual, different, fantastic, original,

imaginative, strange", etcetera. Unfortunately and to my disgust, another term that

was used frequently, sometimes by my own mother, was "crazy". And there was the comic

strip that tilled the fertile pathways of by brain: Buck Rogers in the 25th

Century. (Flash Gordon came a few years later when I was already hooked.)

The radio shows, with the few rather rudimentary science fiction serials, made their

contributions to my tastes. In my freshman year in high school, I began writing those

"crazy" stories myself as classwork, for which I received some good grades, some bad

grades. When I was eleven and twelve years old,

I had not yet discovered that science fiction was a very special genre of fiction with

a very serious aspect. Tom Swift and John Carter and Lord Greystroke represented for

the Wells-Verne imagination in popular, contemporary print. As I approached my teens,

I was verbally spinning horror stories to my chums in the Kyle's back yard orchard, as

inspired by Dracula (1930), Frankenstein (1931), Dr. Jekyll and Mr.

Hyde (1931), Dr. X (1932), etcetera. By age thirteen, however, fairy tales

for me were growing more and more real. I was slipping into the universe of science

fiction. Here were stories more fascinating and intellectually more provocative than I

had previously imagined. I didn't know, at the time, what this kind of literature was

called. There were many identifications, such as Wells' "scientific romances",

Verne's "extraordinary voyages", Appleton's simple yarns of young inventor Tom Swift,

Burroughs' swashbuckling adventures in other worlds that were in, on and off Earth,

and a host of descriptions with worlds like "unusual, different, fantastic, original,

imaginative, strange", etcetera. Unfortunately and to my disgust, another term that

was used frequently, sometimes by my own mother, was "crazy". And there was the comic

strip that tilled the fertile pathways of by brain: Buck Rogers in the 25th

Century. (Flash Gordon came a few years later when I was already hooked.)

The radio shows, with the few rather rudimentary science fiction serials, made their

contributions to my tastes. In my freshman year in high school, I began writing those

"crazy" stories myself as classwork, for which I received some good grades, some bad

grades.

I was not in the vanguard of aficionados.

Older boys in high school (always, in those days of over half century ago they were

"boys") had discovered thls "new" genre ahead of me. I first became conscious of this

genesis of "fandom" by overhearing street conversations on warm spring and summer nights

under the street light outside my open, second floor window while I did homework. There

were arguments about all kinds of remarkable things, such as the possibility of space

travel. It was from one of these mature, sophisticated "older boys" (two years, three

years older?) that I found my first true science fiction magazine. I was not in the vanguard of aficionados.

Older boys in high school (always, in those days of over half century ago they were

"boys") had discovered thls "new" genre ahead of me. I first became conscious of this

genesis of "fandom" by overhearing street conversations on warm spring and summer nights

under the street light outside my open, second floor window while I did homework. There

were arguments about all kinds of remarkable things, such as the possibility of space

travel. It was from one of these mature, sophisticated "older boys" (two years, three

years older?) that I found my first true science fiction magazine.

About the time I entered high school, I

became a regular sf reader with my discovery of the Gernsback magazines, Science

Wonder Stories and Air Wonder Stories, and the older Amazing Stories.

They were back issues because the time was 1932, two years after the first two had been

consolidated into Wonder Stories and when Amazing was no longer a

Gernsback publication. About the time I entered high school, I

became a regular sf reader with my discovery of the Gernsback magazines, Science

Wonder Stories and Air Wonder Stories, and the older Amazing Stories.

They were back issues because the time was 1932, two years after the first two had been

consolidated into Wonder Stories and when Amazing was no longer a

Gernsback publication.

In the early thirties, The Great

Depression was getting worse, affecting the entire nation, forcing young people into

frugality. There were just three exclusively-SF magazines being published and available

on the newsstands in those years, Amazing, Wonder, and Astounding

Stories. Occasionally SF appeared in Weird Tales, Argosy, and such

other monthly or weekly pulps. I could regularly buy only Wonder Stories of

those which appeared. Used magazines, with much borrowing and lending, were the prime

source for us teenagers. I lived in a small town. There were no "second hand" book

stores there, but once in a while I got to New York City with my mother and bought my

supply of old copies, with disfigured covers, torn covers, and even (alas!) no cover. In the early thirties, The Great

Depression was getting worse, affecting the entire nation, forcing young people into

frugality. There were just three exclusively-SF magazines being published and available

on the newsstands in those years, Amazing, Wonder, and Astounding

Stories. Occasionally SF appeared in Weird Tales, Argosy, and such

other monthly or weekly pulps. I could regularly buy only Wonder Stories of

those which appeared. Used magazines, with much borrowing and lending, were the prime

source for us teenagers. I lived in a small town. There were no "second hand" book

stores there, but once in a while I got to New York City with my mother and bought my

supply of old copies, with disfigured covers, torn covers, and even (alas!) no cover.

Through Wonder's readers' columns

I became part of "fandom", that glorious anarchistic fraternity of enthusiasts which

was just developing. This began my active participation. I regularly sent Ietters to

the editors telling them what was good or bad about their publications. Like so many

of the other young letter writers, I was very enthusiastic and very opinionated and

often sounded a bit of a prig. In my heart I knew I could probably choose and edit

and even write better stories. I kept a personal rating chart of sf stories and authors,

along with brief biographies and portrait sketches. Then in 1935, at the age of 16,

when I was a Junior in Monticello (N.Y.) High School, I wrote a "serious" short story.

I entitled it "Golden Nemesis", referring to the color of the serum and what happened

with its use. I submitted it to -- what else? -- my cherished pulp periodical published

by my hero Hugo Gernsback. It was, in retrospect, a rather badly written story, but

it had an original idea, and to my enormous surprise and pleasure I received a letter

from the managing editor, Charles D. Hornig, accepting it without change. Through Wonder's readers' columns

I became part of "fandom", that glorious anarchistic fraternity of enthusiasts which

was just developing. This began my active participation. I regularly sent Ietters to

the editors telling them what was good or bad about their publications. Like so many

of the other young letter writers, I was very enthusiastic and very opinionated and

often sounded a bit of a prig. In my heart I knew I could probably choose and edit

and even write better stories. I kept a personal rating chart of sf stories and authors,

along with brief biographies and portrait sketches. Then in 1935, at the age of 16,

when I was a Junior in Monticello (N.Y.) High School, I wrote a "serious" short story.

I entitled it "Golden Nemesis", referring to the color of the serum and what happened

with its use. I submitted it to -- what else? -- my cherished pulp periodical published

by my hero Hugo Gernsback. It was, in retrospect, a rather badly written story, but

it had an original idea, and to my enormous surprise and pleasure I received a letter

from the managing editor, Charles D. Hornig, accepting it without change.

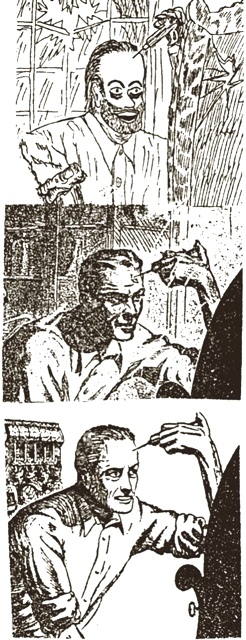

When I had recovered, after a few days,

I immediately set about drawing an illustration for it. The idea that I could display

another talent of mine was a temptation so strong that I was willing to sacrifice an

exceptional honor. I would give up the chance to have the great Frank R. Paul

illustrate my creation. I would have my very own illustration for my very own story

in Gernsback's unique Wonder magazine, another dream of glory by a callow

youth. When I had recovered, after a few days,

I immediately set about drawing an illustration for it. The idea that I could display

another talent of mine was a temptation so strong that I was willing to sacrifice an

exceptional honor. I would give up the chance to have the great Frank R. Paul

illustrate my creation. I would have my very own illustration for my very own story

in Gernsback's unique Wonder magazine, another dream of glory by a callow

youth.

Frank R. Paul was a man who dominated

the science fiction field with his artwork. He was probably more intensely honored

by the readership than Hugo Gernsback. He was an incredibly prolific illustrator,

both in color and in black and white. To me he certainly was, as he was billed on

the magazine contents pages, "inimitable". He had loyally tied his career with

Gernsback's for decades. Paul was the essence of the science fiction imagination of

the century and I considered him of heroic stature. The year previous to my Golden

story submission, I had met Paul accidentally while visiting the Wonder

offices to pay adolescent homage to the editors. He was very kind to the

hero-worshiping boy, looking up from his drawing board, a white-haired gentleman who

now captivated me personally as well as artistically. Frank R. Paul was a man who dominated

the science fiction field with his artwork. He was probably more intensely honored

by the readership than Hugo Gernsback. He was an incredibly prolific illustrator,

both in color and in black and white. To me he certainly was, as he was billed on

the magazine contents pages, "inimitable". He had loyally tied his career with

Gernsback's for decades. Paul was the essence of the science fiction imagination of

the century and I considered him of heroic stature. The year previous to my Golden

story submission, I had met Paul accidentally while visiting the Wonder

offices to pay adolescent homage to the editors. He was very kind to the

hero-worshiping boy, looking up from his drawing board, a white-haired gentleman who

now captivated me personally as well as artistically.

I was no Paul. My illustration, a

very oversized, much too detailed line drawing, was rejected. I was no Paul. My illustration, a

very oversized, much too detailed line drawing, was rejected.

Meanwhile, the intolerable waiting had

begun. The next issue, of course, did not see me in print. Then came an issue in

which my story was advertised as forthcoming. But the next issue didn't contain my

work, either. Meanwhile, the intolerable waiting had

begun. The next issue, of course, did not see me in print. Then came an issue in

which my story was advertised as forthcoming. But the next issue didn't contain my

work, either.

Suddenly my dream disintegrated.

Wonder was sold. Hugo Gernsback was out of the science fiction business.

After a while, a new, revamped magazine entitied Thrilling Wonder Stories

appeared with a different editorial policy and my story was returned. I didn't

get back just the manuscript. Oh, joy, oh sadness! I received the Wonder

Stories page proofs of my story, not galley proofs, but page proofs

distinctively formatted with editorial introduction! And with a full page

illustration by Charles Schneeman! I was a Gernsback author in print yet never

to he published and my disappointment as a teenager was crushing. To add to the

terrible sense of loss was the recognition that my illustration had, in effect,

been redrawn by Schneeman. There it was, the hero with his shaved head, injecting

himself, needle in his brow, staring in a mirror, just as I had pictured it --

layout, fancy angle, shading and all. Had Schneeman copied my illustration or

had he by a strange coincidence visualized the scene as I had? The real difference,

and it was an enormous difference, was that his work was professionally excellent

and mine as obviously amateurish. Suddenly my dream disintegrated.

Wonder was sold. Hugo Gernsback was out of the science fiction business.

After a while, a new, revamped magazine entitied Thrilling Wonder Stories

appeared with a different editorial policy and my story was returned. I didn't

get back just the manuscript. Oh, joy, oh sadness! I received the Wonder

Stories page proofs of my story, not galley proofs, but page proofs

distinctively formatted with editorial introduction! And with a full page

illustration by Charles Schneeman! I was a Gernsback author in print yet never

to he published and my disappointment as a teenager was crushing. To add to the

terrible sense of loss was the recognition that my illustration had, in effect,

been redrawn by Schneeman. There it was, the hero with his shaved head, injecting

himself, needle in his brow, staring in a mirror, just as I had pictured it --

layout, fancy angle, shading and all. Had Schneeman copied my illustration or

had he by a strange coincidence visualized the scene as I had? The real difference,

and it was an enormous difference, was that his work was professionally excellent

and mine as obviously amateurish.

Years later my friend Donald A.

Wollheim finally published the story in the first issue of Stirring Science

Stories, a magazine which he created and edited. The prose was unchanged, as

poorly constructed as my inexperienced talent had originally produced, but this

time the illustration was drawn by me, vastly improved because I had reworked

Schneeman's art as I believed he had reworked mine. Years later my friend Donald A.

Wollheim finally published the story in the first issue of Stirring Science

Stories, a magazine which he created and edited. The prose was unchanged, as

poorly constructed as my inexperienced talent had originally produced, but this

time the illustration was drawn by me, vastly improved because I had reworked

Schneeman's art as I believed he had reworked mine.

Although I had some contact with

Hugo Gernsback in later years, I never did publicly become one of his published

discoveries. Ironically, however, I did get a Frank R. Paul illustration twenty

years later when, for me, he graciously did a letterhead for the World Science

Fiction Convention in New York City in 1956 when I was its chairman. Although I had some contact with

Hugo Gernsback in later years, I never did publicly become one of his published

discoveries. Ironically, however, I did get a Frank R. Paul illustration twenty

years later when, for me, he graciously did a letterhead for the World Science

Fiction Convention in New York City in 1956 when I was its chairman.

"Golden Nemesis" was written in

the glorious autumn of 1935. It was accepted (and not to be paid for until

publication) in the glorious winter of 1935-36 by editor Charles D. Hornig who

was himself a fan, a very young man whose fanzine had impressed Gernsback enough

to be hired. My "Nemesis" was returned in the catastrophic spring of 1936 by

the youthful editor of Standard Magazines' Thrilling Wonder, Mort

Weisinger, who was himself a fan -- what many fateful coincidences have come

about here! A half century 1ater, at the 1988 World Science Fiction Convention

in New Orleans, Charlie Hornig and myself both appeared to the audience as newly

elected to the First Fandom Hall of Fame and given our commemorative plaques.

And standing with us for the same honor was Julius Schwartz, long time associate

and close friend of the late Mort Weisinger! "Golden Nemesis" was written in

the glorious autumn of 1935. It was accepted (and not to be paid for until

publication) in the glorious winter of 1935-36 by editor Charles D. Hornig who

was himself a fan, a very young man whose fanzine had impressed Gernsback enough

to be hired. My "Nemesis" was returned in the catastrophic spring of 1936 by

the youthful editor of Standard Magazines' Thrilling Wonder, Mort

Weisinger, who was himself a fan -- what many fateful coincidences have come

about here! A half century 1ater, at the 1988 World Science Fiction Convention

in New Orleans, Charlie Hornig and myself both appeared to the audience as newly

elected to the First Fandom Hall of Fame and given our commemorative plaques.

And standing with us for the same honor was Julius Schwartz, long time associate

and close friend of the late Mort Weisinger!

The question has always bothered

me because there was no authority to give me the answer: had I really been a part

of those remarkable years of Wonder? Or had I merely scored an unfortunate

near miss? Then in 1989 came an unsolicited judgement. The British researcher

and biographer, Michael Ashley, an editor and compiler of many historical books

about science fiction, sent me a letter to inform me about his next work now in

progress, a book about Hugo Gernsback. He wrote: "It wasn't til I poured through

the small print of Wonder Stories that I realized or remembered that you

had indeed sold a story to Gernsback, 'Golden Nemesis', that for several months

was announced as forthcoming but which never was used and only finally appeared

five years later in Stirring Science Stories. But published or not, it

makes you a Gernsback author." Yes, Virginia, Santa Claus is real and so is that

teenage author -- me, David A. Kyle -- a GERNSBACK author. The question has always bothered

me because there was no authority to give me the answer: had I really been a part

of those remarkable years of Wonder? Or had I merely scored an unfortunate

near miss? Then in 1989 came an unsolicited judgement. The British researcher

and biographer, Michael Ashley, an editor and compiler of many historical books

about science fiction, sent me a letter to inform me about his next work now in

progress, a book about Hugo Gernsback. He wrote: "It wasn't til I poured through

the small print of Wonder Stories that I realized or remembered that you

had indeed sold a story to Gernsback, 'Golden Nemesis', that for several months

was announced as forthcoming but which never was used and only finally appeared

five years later in Stirring Science Stories. But published or not, it

makes you a Gernsback author." Yes, Virginia, Santa Claus is real and so is that

teenage author -- me, David A. Kyle -- a GERNSBACK author.

Illustrations by Alan Hutchinson, Dave Kyle, and

Charles Schneeman

|