Speaking of transitions, it

occurs to us that we've already been running a series of articles describing

a kind of transition -- that of the first few years in one's chosen profession.

(Maybe we have stumbled onto a theme for this issue, after all...) We

received this article not long before the Boston Worldcon, which not only allowed

us to find out for ourselves that she still has lots of entertaining stories left

about the medical profession, it shows you how long this issue of Mimosa has

been in transition between the Post Office and the mimeograph. The seasons really

do speed by here in the Washington area... Speaking of transitions, it

occurs to us that we've already been running a series of articles describing

a kind of transition -- that of the first few years in one's chosen profession.

(Maybe we have stumbled onto a theme for this issue, after all...) We

received this article not long before the Boston Worldcon, which not only allowed

us to find out for ourselves that she still has lots of entertaining stories left

about the medical profession, it shows you how long this issue of Mimosa has

been in transition between the Post Office and the mimeograph. The seasons really

do speed by here in the Washington area...

- - - - - - - -

Tales of Adventure and

Medical Life (Part

III)

by Sharon Farber

by Sharon Farber

Take him to Bliss. Take him to Bliss.

Say it like Sidney Greenstreet,

and it's threatening -- send him to his ultimate reward! Say it like Peter Lorre,

it's not quite as threatening -- give him some obscure oriental drug that will

disarrange his thinking. Perhaps permanently? Pity... Say it like Sidney Greenstreet,

and it's threatening -- send him to his ultimate reward! Say it like Peter Lorre,

it's not quite as threatening -- give him some obscure oriental drug that will

disarrange his thinking. Perhaps permanently? Pity...

When a doctor in St. Louis says

take him to Bliss, it means "take him to the local public mental hospital,

and lock him up." When a doctor in St. Louis says

take him to Bliss, it means "take him to the local public mental hospital,

and lock him up."

Malcolm Bliss Mental Health Center

was one block away from City Hospital, but not a block you'd particularly want to

walk, let alone at night. A tunnel connected the two hospitals, but I'm told that

was even worse. A drunk is supposed to have wandered into the tunnel system a few

years ago, and was eventually found dead. In any event, the roaches in the

basement were as big as a respectable mouse, and I had no desire to meet the

mice. Malcolm Bliss Mental Health Center

was one block away from City Hospital, but not a block you'd particularly want to

walk, let alone at night. A tunnel connected the two hospitals, but I'm told that

was even worse. A drunk is supposed to have wandered into the tunnel system a few

years ago, and was eventually found dead. In any event, the roaches in the

basement were as big as a respectable mouse, and I had no desire to meet the

mice.

Medical students spent a month at

Bliss, and then two weeks in the more refined private psychiatric pavilions at the

university, with an entirely different patient population. At the university, the

patients were still functional enough to have insurance, or relatives with

insurance. Some did not even need to be hospitalized -- they just wanted a

vacation from responsibility. I once heard my attending have a long conversation

with one of his patients, explaining that it would be at least two weeks before

she could get a reservation. Medical students spent a month at

Bliss, and then two weeks in the more refined private psychiatric pavilions at the

university, with an entirely different patient population. At the university, the

patients were still functional enough to have insurance, or relatives with

insurance. Some did not even need to be hospitalized -- they just wanted a

vacation from responsibility. I once heard my attending have a long conversation

with one of his patients, explaining that it would be at least two weeks before

she could get a reservation.

Patients at Bliss, on the other

hand, were usually dragged in kicking and screaming by families or police, or

(in the case of the chronic patients) shuffled in on their own when life got too

tough. You knew this was going to happen when there was a "positive suitcase

sign". (It is difficult to persuade someone who has brought his suitcase that he

doesn't really need to be in hospital. A friend once saw two people with

suitcases out in the waiting room. He was quite upset, knowing this meant two

admissions. But it turned out the patients knew each other, and by the time my

friend decided he could no longer put off speaking with them, they'd gone off

together to have fun.) Patients at Bliss, on the other

hand, were usually dragged in kicking and screaming by families or police, or

(in the case of the chronic patients) shuffled in on their own when life got too

tough. You knew this was going to happen when there was a "positive suitcase

sign". (It is difficult to persuade someone who has brought his suitcase that he

doesn't really need to be in hospital. A friend once saw two people with

suitcases out in the waiting room. He was quite upset, knowing this meant two

admissions. But it turned out the patients knew each other, and by the time my

friend decided he could no longer put off speaking with them, they'd gone off

together to have fun.)

Most of the patients were

schizophrenics of all variety, maniacs, and depressives, though you had to be

incredibly depressed to get into Bliss. It helped to be catatonic. There were

also a fair number of violent and unsavory individuals in for forensic evaluation.

I was warned to never go into the wards alone; on the other hand, the orderlies

would never accompany me, so I did anyway. Most of the patients were

schizophrenics of all variety, maniacs, and depressives, though you had to be

incredibly depressed to get into Bliss. It helped to be catatonic. There were

also a fair number of violent and unsavory individuals in for forensic evaluation.

I was warned to never go into the wards alone; on the other hand, the orderlies

would never accompany me, so I did anyway.

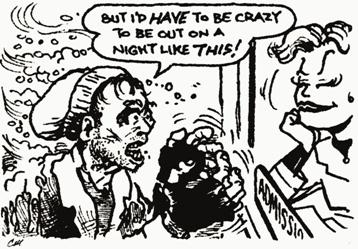

Another class of patients that

frequented the hospital were down and outs -- drunks, sociopaths, the mildly

psychotic -- who had learned to abuse the system. They would present on a cold

night, recite the proper litany of symptoms to earn admission, sleep in a warm bed,

enjoy a couple of meals (Bliss had the best hospital food in town) and then check

out. Hotel Bliss we called it. Another class of patients that

frequented the hospital were down and outs -- drunks, sociopaths, the mildly

psychotic -- who had learned to abuse the system. They would present on a cold

night, recite the proper litany of symptoms to earn admission, sleep in a warm bed,

enjoy a couple of meals (Bliss had the best hospital food in town) and then check

out. Hotel Bliss we called it.

Naturally, this made us furious.

Not only did an admission entail an extraordinary amount of work -- complete

history, physical, review of prior charts, paperwork galore -- but this usually

occurred in the dead of the night, when you'd rather he sleeping. And it took

up beds that might have been occupied by those actually ill. Many times, real

patients were turned away for lack of room. Naturally, this made us furious.

Not only did an admission entail an extraordinary amount of work -- complete

history, physical, review of prior charts, paperwork galore -- but this usually

occurred in the dead of the night, when you'd rather he sleeping. And it took

up beds that might have been occupied by those actually ill. Many times, real

patients were turned away for lack of room.

One of my housemates enjoyed a brief

reputation for heroic tough-mindedness when she got rid of one such patient. He was

an alcoholic with a long history of checking in overnight. It was impossible to

summarily dismiss him as he had, through trial and error, hit upon the exact words

that were guaranteed to gain him admission. "I'm going to kill myself," he would

say. One of my housemates enjoyed a brief

reputation for heroic tough-mindedness when she got rid of one such patient. He was

an alcoholic with a long history of checking in overnight. It was impossible to

summarily dismiss him as he had, through trial and error, hit upon the exact words

that were guaranteed to gain him admission. "I'm going to kill myself," he would

say.

It's very hard to get rid of someone

threatening suicide. (Just a hint to those of our readers who may someday be

destitute and looking for a free room and board. If you don't mind being held

against your will and given drugs and perhaps shock therapy in return.) Of course,

a phenomenal proportion of those who threaten or attempt suicide (usually in fairly

benign ways -- many people who succeed in suicide are quite surprised) are hysterics

and sociopaths just doing it to manipulate others. It's very hard to get rid of someone

threatening suicide. (Just a hint to those of our readers who may someday be

destitute and looking for a free room and board. If you don't mind being held

against your will and given drugs and perhaps shock therapy in return.) Of course,

a phenomenal proportion of those who threaten or attempt suicide (usually in fairly

benign ways -- many people who succeed in suicide are quite surprised) are hysterics

and sociopaths just doing it to manipulate others.

Anyway, my housemate asked this

drunk: "How do you plan to kill yourself?" The man -- taken a bit aback, he thought

he'd be cozy in bed by this point -- said, "Well, I'll jump off a bridge." Anyway, my housemate asked this

drunk: "How do you plan to kill yourself?" The man -- taken a bit aback, he thought

he'd be cozy in bed by this point -- said, "Well, I'll jump off a bridge."

"Which one?" asked my friend. There

are several in St. Louis, not counting overpasses. "Which one?" asked my friend. There

are several in St. Louis, not counting overpasses.

"I don't know"" the man replied,

rather annoyed. "I don't know"" the man replied,

rather annoyed.

No suicidal plans, she wrote and

booted him. No suicidal plans, she wrote and

booted him.

#

My first trip to the wards at Bliss was

illuminating. I unlocked the door, walked in, and was promptly surrounded by a half

dozen schizophrenic, disheveled, expressionless, shambling persons of various races

and sexes. "Doctor, I want a pass." "Doctor, I need cigarettes." I quickly took

refuge inside the nurses station, which was surrounded on three sides by huge glass

windows, lined with patients demanding cigarettes. It was a lot like a fishbowl, or

feeding time at the zoo. My first trip to the wards at Bliss was

illuminating. I unlocked the door, walked in, and was promptly surrounded by a half

dozen schizophrenic, disheveled, expressionless, shambling persons of various races

and sexes. "Doctor, I want a pass." "Doctor, I need cigarettes." I quickly took

refuge inside the nurses station, which was surrounded on three sides by huge glass

windows, lined with patients demanding cigarettes. It was a lot like a fishbowl, or

feeding time at the zoo.

Eventually, I learned the proper way

to enter the ward. You unlocked the door and headed in with enough momentum to plunge

you through the wall of supplicants and into the conference room, whose door you kicked

shut behind you. I learned to juggle in that room. Eventually, I learned the proper way

to enter the ward. You unlocked the door and headed in with enough momentum to plunge

you through the wall of supplicants and into the conference room, whose door you kicked

shut behind you. I learned to juggle in that room.

Soon after my arrival, I was assigned

to do an admission physical on a paranoid schizophrenic who had bounced back into the

hospital. It went rather uneventfully until I decided to check his Babinski reflex.

This entailed removing his stockings. I stared in amazement as the putrid hole-ridden

socks peeled off his feet but maintained a foot shape. They were stiff with dirt.

Their color was an ill-defined shade somewhere between filth and Kelly green. Soon after my arrival, I was assigned

to do an admission physical on a paranoid schizophrenic who had bounced back into the

hospital. It went rather uneventfully until I decided to check his Babinski reflex.

This entailed removing his stockings. I stared in amazement as the putrid hole-ridden

socks peeled off his feet but maintained a foot shape. They were stiff with dirt.

Their color was an ill-defined shade somewhere between filth and Kelly green.

"Well," I said. "They're

certainly...green." "Well," I said. "They're

certainly...green."

"Yes," said the man. Up to now he'd

been perfectly quiet. "They're green. I'm the Green Hornet." "Yes," said the man. Up to now he'd

been perfectly quiet. "They're green. I'm the Green Hornet."

I allowed that I was pleased to make

his acquaintance. I allowed that I was pleased to make

his acquaintance.

"I'm an architect," he continued. "I

design skyscrapers. Batman does too. He's my archfoe. We have a grudge match." It

turned out he wasn't really the Green Hornet -- he stared at me blankly when I asked

about Kato -- but I decided that maybe Bliss would have its interesting moments. "I'm an architect," he continued. "I

design skyscrapers. Batman does too. He's my archfoe. We have a grudge match." It

turned out he wasn't really the Green Hornet -- he stared at me blankly when I asked

about Kato -- but I decided that maybe Bliss would have its interesting moments.

#

We had not been long at Bliss when my

classmate (the Robot) and I were taken to witness a court hearing. One of our quieter

schizophrenics wanted to leave the hospital, and his family wanted him to stay. He

was a bit violent, but for some reason I never understood, the psychiatrist was not

allowed to testify to that effect. The testimony had to come from family. We had not been long at Bliss when my

classmate (the Robot) and I were taken to witness a court hearing. One of our quieter

schizophrenics wanted to leave the hospital, and his family wanted him to stay. He

was a bit violent, but for some reason I never understood, the psychiatrist was not

allowed to testify to that effect. The testimony had to come from family.

We got to court, and waited. The

family didn't show. Finally, the judge declared the case closed, and instructed us

to release the patient. At that moment, the family straggled in, reeking of liquor.

"Too late," they were told, and this bad news made them belligerent. As we left,

they were beginning a shoving match under the watchful eyes of the bailiffs. We got to court, and waited. The

family didn't show. Finally, the judge declared the case closed, and instructed us

to release the patient. At that moment, the family straggled in, reeking of liquor.

"Too late," they were told, and this bad news made them belligerent. As we left,

they were beginning a shoving match under the watchful eyes of the bailiffs.

#

I suppose, in the good old days,

seriously crazy people did think they were saints, or Satan, or Napoleon. You still

see an amazing amount of religious delusions in the insane, which can lead to problems

in diagnosis. For instance, how do you determine insanity in someone who says she

converses with angels, when everyone else in her church also gets personal advice from

higher powers and speaks in tongues? It turns out that what you do is to go to the

other people in the church, who have the same totally bizarre beliefs, and ask, "Hey,

is she nuts, or what?" I suppose, in the good old days,

seriously crazy people did think they were saints, or Satan, or Napoleon. You still

see an amazing amount of religious delusions in the insane, which can lead to problems

in diagnosis. For instance, how do you determine insanity in someone who says she

converses with angels, when everyone else in her church also gets personal advice from

higher powers and speaks in tongues? It turns out that what you do is to go to the

other people in the church, who have the same totally bizarre beliefs, and ask, "Hey,

is she nuts, or what?"

A surprising number of the delusions I

encountered at Bliss were science-fictional. People with thought-control devices

imbedded in their head; people who were convinced they were robots; strange visitors

from other planets. We even had a Vulcan on our ward, though he did not act in the

least Vulcanish. (When I learned that there was a Vulcan on another ward downstairs,

I suggested we put them together and see what happened. No one was amused.) A surprising number of the delusions I

encountered at Bliss were science-fictional. People with thought-control devices

imbedded in their head; people who were convinced they were robots; strange visitors

from other planets. We even had a Vulcan on our ward, though he did not act in the

least Vulcanish. (When I learned that there was a Vulcan on another ward downstairs,

I suggested we put them together and see what happened. No one was amused.)

One teenaged manic, after we all had

been enjoying hearing how he'd impressed all the Cardinals with his baseball skills,

went on to tell us that he'd constructed a working rocket ship in his backyard. One teenaged manic, after we all had

been enjoying hearing how he'd impressed all the Cardinals with his baseball skills,

went on to tell us that he'd constructed a working rocket ship in his backyard.

"You must've needed some help on a

project that big," said the attending. "Who worked on it with you?" "You must've needed some help on a

project that big," said the attending. "Who worked on it with you?"

The kid shrugged. "Oh, me and God and

some other guys." The kid shrugged. "Oh, me and God and

some other guys."

A few years later, a friend of mine

had a patient who claimed to have a rocket ship inside his brain. My friend did the

logical thing. He called a neurosurgery consult. It took the neurosurgeon -- a

rather nasty gentleman, in the habit of terrorizing his subordinates -- a long time

to comprehend that someone was playing a joke on him. A few years later, a friend of mine

had a patient who claimed to have a rocket ship inside his brain. My friend did the

logical thing. He called a neurosurgery consult. It took the neurosurgeon -- a

rather nasty gentleman, in the habit of terrorizing his subordinates -- a long time

to comprehend that someone was playing a joke on him.

#

After I'd been at Bliss about a week,

it was time to take call in the emergency room. The resident flipped through the stack

of charts, then tossed me one. "Suicidal ideation. Should be easy," he said. "Just

ask him all the questions about depression, then come tell me the history." After I'd been at Bliss about a week,

it was time to take call in the emergency room. The resident flipped through the stack

of charts, then tossed me one. "Suicidal ideation. Should be easy," he said. "Just

ask him all the questions about depression, then come tell me the history."

I went into the examining room, mentally

rehearsing the symptoms of depression (insomnia, anorexia, anhedonia, dysphoria) and

sat down at the desk beside the patient. The man was huge. He looked like a Green

Bay Packer. A sullen Green Bay Packer. I went into the examining room, mentally

rehearsing the symptoms of depression (insomnia, anorexia, anhedonia, dysphoria) and

sat down at the desk beside the patient. The man was huge. He looked like a Green

Bay Packer. A sullen Green Bay Packer.

"So," I said, "you want to kill yourself.

How were you going to do it?" First, let's make sure he's sincere. "So," I said, "you want to kill yourself.

How were you going to do it?" First, let's make sure he's sincere.

"I'm going to drive my car at eighty miles

an hour into another car," he replied, with a total lack of expression. "I'm going to drive my car at eighty miles

an hour into another car," he replied, with a total lack of expression.

"Gee," I said. "Won't that kill someone

else, too?" That was unusual for a depressive. "Gee," I said. "Won't that kill someone

else, too?" That was unusual for a depressive.

The Hulk stared at me. "My voices tell

me to kill people." The Hulk stared at me. "My voices tell

me to kill people."

Oops. Voices. I had the wrong diagnostic

category entirely. This guy wasn't depressed, he was psychotic. Oops. Voices. I had the wrong diagnostic

category entirely. This guy wasn't depressed, he was psychotic.

"Uh, any people in particular?" "Uh, any people in particular?"

He continued to stare at me very

intensely. "My voices tell me to kill women." He continued to stare at me very

intensely. "My voices tell me to kill women."

I began to wish I hadn't sat so far from

the door. "Uh, do you do what your voices tell you?" I began to wish I hadn't sat so far from

the door. "Uh, do you do what your voices tell you?"

"I go down to the Stroll and I hurt

women." "I go down to the Stroll and I hurt

women."

Great. I very casually rose from my

chair and inched towards the door. I needed another couple questions to fill up the

time it would take me to escape. Quick, what were other symptoms of schizophrenia?

Hearing voices, thought insertion, personal messages from the radio or TV.... Great. I very casually rose from my

chair and inched towards the door. I needed another couple questions to fill up the

time it would take me to escape. Quick, what were other symptoms of schizophrenia?

Hearing voices, thought insertion, personal messages from the radio or TV....

"Do you get messages from the TV?" "Do you get messages from the TV?"

"It tells me to kill women." "It tells me to kill women."

Great. I was almost to the

door. "Any shows in particular?" Great. I was almost to the

door. "Any shows in particular?"

"Starsky and Hutch." "Starsky and Hutch."

I zoomed out the door, into the

resident's office, and said, "He likes to kill women!" I zoomed out the door, into the

resident's office, and said, "He likes to kill women!"

"Fine," said my resident. A few

minutes later, he sent me back to do the physical examination. I decided to pass on

the rectal exam. "Fine," said my resident. A few

minutes later, he sent me back to do the physical examination. I decided to pass on

the rectal exam.

#

After Bliss, I did two weeks at the

much classier but also much duller psych ward at a private hospital. One day, as

I was standing at the nurses station on the locked ward, a patient got up from a

game, shuffled over, and placed a stack of playing cards onto the counter. After Bliss, I did two weeks at the

much classier but also much duller psych ward at a private hospital. One day, as

I was standing at the nurses station on the locked ward, a patient got up from a

game, shuffled over, and placed a stack of playing cards onto the counter.

"Nurse," he said, "we need new cards.

We aren't playing with a full deck." "Nurse," he said, "we need new cards.

We aren't playing with a full deck."

#

The strangest thing about medical

education is how it changes you into someone who thinks and does things that you

never would dream yourself capable of. The strangest thing about medical

education is how it changes you into someone who thinks and does things that you

never would dream yourself capable of.

I remember, back around '71, when

Thomas Eagleton had to give up running for Vice President because of the revelation

that he'd been hospitalized for depression and received shock therapy. I had a

typically Californian response to shock therapy. "What sort of barbarians would do

that to a person?" I remember, back around '71, when

Thomas Eagleton had to give up running for Vice President because of the revelation

that he'd been hospitalized for depression and received shock therapy. I had a

typically Californian response to shock therapy. "What sort of barbarians would do

that to a person?"

Well, it turns out that Washington

University at St. Louis was the hotbed of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). And so,

thirteen years after deploring Eagleton's ECT, I found myself, in probably the same

ward where he received it, as the resident administering shock therapy. Well, it turns out that Washington

University at St. Louis was the hotbed of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). And so,

thirteen years after deploring Eagleton's ECT, I found myself, in probably the same

ward where he received it, as the resident administering shock therapy.

However, I was probably the only

neurology resident in the history of the hospital to deliver shock while shouting,

"Fire phaser, Scotty!" However, I was probably the only

neurology resident in the history of the hospital to deliver shock while shouting,

"Fire phaser, Scotty!"

Some people are crazy on the psych

ward, and I'm not just talking about the patients. Some people are crazy on the psych

ward, and I'm not just talking about the patients.

All illustrations by Charlie Williams

|