We didn't think that this 'Welcome to the Future' issue of Mimosa would be

complete without an article about one of the world's most famous futurists, Arthur

C. Clarke. Back in 1968, the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, based in part on

Clarke's superb short story, "The Sentinel," gave us all a stunning vision of what

the future might hold. At that time, he had been a professional science fiction

writer for more than two decades. But what's less well known is about him is that

he had been a fan for more than 15 years before his first professional sale. Here's

more about...

We didn't think that this 'Welcome to the Future' issue of Mimosa would be

complete without an article about one of the world's most famous futurists, Arthur

C. Clarke. Back in 1968, the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, based in part on

Clarke's superb short story, "The Sentinel," gave us all a stunning vision of what

the future might hold. At that time, he had been a professional science fiction

writer for more than two decades. But what's less well known is about him is that

he had been a fan for more than 15 years before his first professional sale. Here's

more about...

Here's a legitimate question: Is

there an example of a typical genesis for a 'dinosaur' of First Fandom? Here's a legitimate question: Is

there an example of a typical genesis for a 'dinosaur' of First Fandom?

Consider this personal statement:

"Sometime towards the end of 1930, in my thirteenth year, I acquired my first

science fiction magazine -- and my life was irrevocably changed." Consider this personal statement:

"Sometime towards the end of 1930, in my thirteenth year, I acquired my first

science fiction magazine -- and my life was irrevocably changed."

Right on! Bull's-eye! Right on! Bull's-eye!

This confession marks the rousing

beginning of a passionate science fiction fan. With few factual changes it could be

the soulful admission of most any old-timer of First Fandom. It applied to me just

two and a half years later in 1933, then also aged thirteen. Actually, however,

this quote is the forthright state ment of Arthur C. Clarke, printed as the opening

sentence of his 1989 book Astounding Days. This confession marks the rousing

beginning of a passionate science fiction fan. With few factual changes it could be

the soulful admission of most any old-timer of First Fandom. It applied to me just

two and a half years later in 1933, then also aged thirteen. Actually, however,

this quote is the forthright state ment of Arthur C. Clarke, printed as the opening

sentence of his 1989 book Astounding Days.

What was the magazine which launched

him into our fannish sf world? Obviously, by his book's title, it was Astounding

Stories of Super Science. The boy had found an issue of that pioneering pulp,

abandoned, in a room of his Huish's Grammar School in Somerset, England. There was

no date on the cover, a marketing tactic by Clayton Publications which editor Harry

Bates used monthly from its beginning, in January 1930, to nearly the end of

1931. What was the magazine which launched

him into our fannish sf world? Obviously, by his book's title, it was Astounding

Stories of Super Science. The boy had found an issue of that pioneering pulp,

abandoned, in a room of his Huish's Grammar School in Somerset, England. There was

no date on the cover, a marketing tactic by Clayton Publications which editor Harry

Bates used monthly from its beginning, in January 1930, to nearly the end of

1931.

This pulp was, in fact, only the

third issue, dated March 1930. It began Arthur C. Clarke's enthusiastic search for

other such American magazines. Surprisingly, his opportunities in England were

many. A welter of pulps were to be found randomly scattered around country stores,

having been imported in bulk and dumped throughout the United Kingdom in the heyday

of those popular, throwaway magazines. This pulp was, in fact, only the

third issue, dated March 1930. It began Arthur C. Clarke's enthusiastic search for

other such American magazines. Surprisingly, his opportunities in England were

many. A welter of pulps were to be found randomly scattered around country stores,

having been imported in bulk and dumped throughout the United Kingdom in the heyday

of those popular, throwaway magazines.

The typically garish Clayton cover on

this issue was by Wesso for the Ray Cummings story "Brigands of the Moon." That

single magazine, as a foundling, turned him into a true fan and began his cherished

collection. Years later, in retrospect, keyed by his mature recollections of his

childhood friendship with the neighborhood Krille family, he belatedly recognized a

remarkable fact: this life-changing discovery might have come sooner. Two years

before that Astounding, he had been exposed to the original scientifiction

virus and he hadn't succumbed. The typically garish Clayton cover on

this issue was by Wesso for the Ray Cummings story "Brigands of the Moon." That

single magazine, as a foundling, turned him into a true fan and began his cherished

collection. Years later, in retrospect, keyed by his mature recollections of his

childhood friendship with the neighborhood Krille family, he belatedly recognized a

remarkable fact: this life-changing discovery might have come sooner. Two years

before that Astounding, he had been exposed to the original scientifiction

virus and he hadn't succumbed.

It might well have been Hugo

Gernsback instead of Harry Bates who set him on his science fiction way. The

middle-aged Larry Krille, now seen as an early, unrecognized prototypical sf

enthusiast, had, back then, lent the young, precocious Arthur one of Hugo Gernsback's

Amazing Stories. The time, how ever, hadn't been ripe for him -- he had

merely skimmed it. Many years later, recollecting his beginnings as an

eleven-year-old, Arthur rediscovered and reconsidered that Amazing Stories

issue for November 1928. However belatedly, he was excited by that lost moment --

the 1928 Frank R. Paul cover was incredible to him because the painting so accurately

depicted the appearance of the planet Jupiter, with its swirling clouds and Great

Red Spot, as viewed by human beings standing on Ganymede. It might well have been Hugo

Gernsback instead of Harry Bates who set him on his science fiction way. The

middle-aged Larry Krille, now seen as an early, unrecognized prototypical sf

enthusiast, had, back then, lent the young, precocious Arthur one of Hugo Gernsback's

Amazing Stories. The time, how ever, hadn't been ripe for him -- he had

merely skimmed it. Many years later, recollecting his beginnings as an

eleven-year-old, Arthur rediscovered and reconsidered that Amazing Stories

issue for November 1928. However belatedly, he was excited by that lost moment --

the 1928 Frank R. Paul cover was incredible to him because the painting so accurately

depicted the appearance of the planet Jupiter, with its swirling clouds and Great

Red Spot, as viewed by human beings standing on Ganymede.

Golly, gee! That Paul-Gernsback

excitement was just like this writer's own initial, juvenile experience at the age

of thirteen with a back issue of the very first Science Wonder Stories and

it's thrilling Paul cover! Golly, gee! That Paul-Gernsback

excitement was just like this writer's own initial, juvenile experience at the age

of thirteen with a back issue of the very first Science Wonder Stories and

it's thrilling Paul cover!

Early fans like me have much in

common with the youthful days of Arthur. There is a pleasant symmetry to our two

lives: In 1936, Arthur left home to go to the big city of London and joined into a

long-lasting social relationship with the famous urban sf fans of the time. In 1936,

I also left home and found a similarity in New York City. In January 1937, Arthur

made a train trip to Leeds with certain sf pals to attend 'the first (organized)

science fiction convention ever'. Two months earlier, I had made a train trip to

Philadelphia with sf pals to attend 'the first (spontaneous) science fiction

convention ever'. Just before World War II, Arthur shared an apartment in London

with William F. Temple and occasional fellow fans -- as I also did in New York about

the same time with Dick Wilson. Our convention-going coincided in 1956 when had I

chosen Arthur as my Worldcon Guest of Honor (Honour?) and we sat together at the

banquet's head table, he just then a Hugo winner for "The Star." In 1969, I came

from upstate New York and he came from England to share in the memorable Apollo 11

moon shot at Cape Canaveral. A few years later, when I was reorganizing the British

Science Fiction Association as its Managing Director, he accepted the position of

Honorary President. Obviously, Arthur and I have shared fandom for our life times.

Decade after decade, the old timers and new comers both knew Arthur more as a

genuine fan rather than a prominent fiction and non-fiction writer. Early fans like me have much in

common with the youthful days of Arthur. There is a pleasant symmetry to our two

lives: In 1936, Arthur left home to go to the big city of London and joined into a

long-lasting social relationship with the famous urban sf fans of the time. In 1936,

I also left home and found a similarity in New York City. In January 1937, Arthur

made a train trip to Leeds with certain sf pals to attend 'the first (organized)

science fiction convention ever'. Two months earlier, I had made a train trip to

Philadelphia with sf pals to attend 'the first (spontaneous) science fiction

convention ever'. Just before World War II, Arthur shared an apartment in London

with William F. Temple and occasional fellow fans -- as I also did in New York about

the same time with Dick Wilson. Our convention-going coincided in 1956 when had I

chosen Arthur as my Worldcon Guest of Honor (Honour?) and we sat together at the

banquet's head table, he just then a Hugo winner for "The Star." In 1969, I came

from upstate New York and he came from England to share in the memorable Apollo 11

moon shot at Cape Canaveral. A few years later, when I was reorganizing the British

Science Fiction Association as its Managing Director, he accepted the position of

Honorary President. Obviously, Arthur and I have shared fandom for our life times.

Decade after decade, the old timers and new comers both knew Arthur more as a

genuine fan rather than a prominent fiction and non-fiction writer.

I didn't meet Arthur in person until

the early spring of 1952. We were both officers in our countries' Air Forces in

England during the war years of 1943-45, but were otherwise occupied than in fandom.

Seven years later, our meeting place was in Bellefontaine, Ohio, and the occasion

was the Easter weekend gathering at Beatley's-on-the-Lake for one of the earliest of

MidWestCons. I didn't meet Arthur in person until

the early spring of 1952. We were both officers in our countries' Air Forces in

England during the war years of 1943-45, but were otherwise occupied than in fandom.

Seven years later, our meeting place was in Bellefontaine, Ohio, and the occasion

was the Easter weekend gathering at Beatley's-on-the-Lake for one of the earliest of

MidWestCons.

That year of 1952 was Arthur's

initial trip to America. His first hardcover sf book, The Sands of Mars,

published by Gnome Press (me and the earlier 'other' Martin Greenberg), was appearing

that year, but the royalties were not enough to finance his trip. It was actually

the success of his non-fiction book, chosen by the Book-of-the-Month Club, that made

his trip possible. This was the year that I identify as the real beginning of his

professional career. That year of 1952 was Arthur's

initial trip to America. His first hardcover sf book, The Sands of Mars,

published by Gnome Press (me and the earlier 'other' Martin Greenberg), was appearing

that year, but the royalties were not enough to finance his trip. It was actually

the success of his non-fiction book, chosen by the Book-of-the-Month Club, that made

his trip possible. This was the year that I identify as the real beginning of his

professional career.

That special year of 1952, to my mind,

also established him as a sf fan of worldwide fame. That spring, he made a big

splash in my fannish memory as a trufan by jumping into Beatley's Indian Lake early

on Sunday morning, not long after many of us had gone to bed. It reflected his

British heritage. It demonstrated his individuality. It also startled his new

American acquaintances. Bear in mind the time of year -- Beatley's was a summer

resort, a big rambling wooden building, closed during the winter, and had opened

early for the season just to accommodate our group. The early spring weather was

chilly at night, and the water was still winter-cold. Arthur was courageous,

enthusiastic, and a powerhouse of physical as well as mental energy. Nothing else

that weekend personified Arthur more nor made such an unshakable, indelible

impression on us all. That special year of 1952, to my mind,

also established him as a sf fan of worldwide fame. That spring, he made a big

splash in my fannish memory as a trufan by jumping into Beatley's Indian Lake early

on Sunday morning, not long after many of us had gone to bed. It reflected his

British heritage. It demonstrated his individuality. It also startled his new

American acquaintances. Bear in mind the time of year -- Beatley's was a summer

resort, a big rambling wooden building, closed during the winter, and had opened

early for the season just to accommodate our group. The early spring weather was

chilly at night, and the water was still winter-cold. Arthur was courageous,

enthusiastic, and a powerhouse of physical as well as mental energy. Nothing else

that weekend personified Arthur more nor made such an unshakable, indelible

impression on us all.

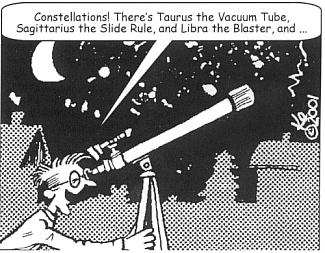

Had Hugo Gernsback only known, he

would have used Arthur as his ideal science fiction reader -- someone who was

involved in every aspect of fandom. Gernsback fervently believed that his

scientifiction mission was the furtherance of science knowledge and experimentation.

That was the love of youthful Arthur, certainly, who did many exceedingly imaginative

home-based projects which foreshadowed the wide range of successes he had later as a

scientist and futurist. The night sky was fascinating to him and construction of

his first telescope from bits and pieces is a testament to his remarkable ingenuity.

He focused on the moon to make it a personal part of his neighborhood, and drew

detailed lunar maps. I, also, at his age was an astronomy buff, like so many other

youthful sf fans, but I merely adapted my father's surveyor's instrument (transit

theodolite) to study our moon and planets. Had Hugo Gernsback only known, he

would have used Arthur as his ideal science fiction reader -- someone who was

involved in every aspect of fandom. Gernsback fervently believed that his

scientifiction mission was the furtherance of science knowledge and experimentation.

That was the love of youthful Arthur, certainly, who did many exceedingly imaginative

home-based projects which foreshadowed the wide range of successes he had later as a

scientist and futurist. The night sky was fascinating to him and construction of

his first telescope from bits and pieces is a testament to his remarkable ingenuity.

He focused on the moon to make it a personal part of his neighborhood, and drew

detailed lunar maps. I, also, at his age was an astronomy buff, like so many other

youthful sf fans, but I merely adapted my father's surveyor's instrument (transit

theodolite) to study our moon and planets.

He and I both had a natural

fascination for space and space travel. Arthur, gaining experience by making

fireworks, once constructed his own miniature rockets. I had my own brief taste of

amateur rocketry, in 1936, as one of the supporting hobbyists of the International

Scientific Association fan club of New York. Old fans have similar stories and it's

a wonder nothing worse than scorched vegetation, clothing, and basements resulted.

In 1933, the British Interplanetary Society was established with perhaps a majority

of the small membership being science fiction-oriented, so it was inevitable that

Arthur, when he migrated to London to get into the mainstream of life, should be

very seriously involved with the fledgling B.I.S., becoming one of its mainstays. He and I both had a natural

fascination for space and space travel. Arthur, gaining experience by making

fireworks, once constructed his own miniature rockets. I had my own brief taste of

amateur rocketry, in 1936, as one of the supporting hobbyists of the International

Scientific Association fan club of New York. Old fans have similar stories and it's

a wonder nothing worse than scorched vegetation, clothing, and basements resulted.

In 1933, the British Interplanetary Society was established with perhaps a majority

of the small membership being science fiction-oriented, so it was inevitable that

Arthur, when he migrated to London to get into the mainstream of life, should be

very seriously involved with the fledgling B.I.S., becoming one of its mainstays.

In the 1930s, London was almost

exclusively the focal point of British fannish life (as London was for most

everything else). Liverpool and Leeds were not yet of importance. And so Arthur

went to London, got a government job and dipped into the frenetic science fiction

scene. Arthur squeezed into London residency, was employed as a civil servant and

made new fannish friends. Friendships grew, groups formed, discussions raged, and

fanzines appeared. As amateur publications proliferated, so did Arthur's

contributions -- he wrote and edited, paid only by the satisfaction of the work.

With his pal and later resident companion, William F. Temple, he co-edited the

famous British fanzine, Novae Terrae. Much like the precocious New York

Futurians who were banded together at this same time in the late 1930s, he and Bill

and the talented Walter H. Gillings and their fellow fans were greatly influencing

fandom and developing into sf professionals simultaneous with the expansion of the

field. Much like the Futurian leader ship of Don Wollheim in U.S. fandom, it was

Wally Gillings, also a bit older, who most shaped London fandom. In the 1930s, London was almost

exclusively the focal point of British fannish life (as London was for most

everything else). Liverpool and Leeds were not yet of importance. And so Arthur

went to London, got a government job and dipped into the frenetic science fiction

scene. Arthur squeezed into London residency, was employed as a civil servant and

made new fannish friends. Friendships grew, groups formed, discussions raged, and

fanzines appeared. As amateur publications proliferated, so did Arthur's

contributions -- he wrote and edited, paid only by the satisfaction of the work.

With his pal and later resident companion, William F. Temple, he co-edited the

famous British fanzine, Novae Terrae. Much like the precocious New York

Futurians who were banded together at this same time in the late 1930s, he and Bill

and the talented Walter H. Gillings and their fellow fans were greatly influencing

fandom and developing into sf professionals simultaneous with the expansion of the

field. Much like the Futurian leader ship of Don Wollheim in U.S. fandom, it was

Wally Gillings, also a bit older, who most shaped London fandom.

Arthur was described in 'those days'

as "pretty thin and tall. He always wore glasses, and he had all his hair then --

lots of wavy, light brown hair. Even today when he speaks, he's got a little bit of

west country burr." Bill Temple thought him "somewhat impatient and highly-strung,

given to sudden violent explosions of mirth." Arthur was described in 'those days'

as "pretty thin and tall. He always wore glasses, and he had all his hair then --

lots of wavy, light brown hair. Even today when he speaks, he's got a little bit of

west country burr." Bill Temple thought him "somewhat impatient and highly-strung,

given to sudden violent explosions of mirth."

In 1938, the London domicile of

Clarke and Temple, 'The Flat', became the natural gathering place for the science

fiction crowd as well as the paralleling B.I.S. group, and the propaganda, fanzines

and space journals were published with the help of all. That house, at 88 Gray's

Inn Road, Bloomsbury, near the British Museum, was remarkably like a mirror of the

fannish world of the Futurians' co-operative Brooklyn apartment, 'The Ivory Tower'.

The two places were each a magnet for the active sf fans in their greater

metropolitan areas. Over here were Don Wollheim, Fred Pohl, Richard Wilson, Dirk

Wylie, Doc Lowndes, Cyril Kornbluth and more. Over there, besides Clarke and Temple

and Maurice Hanson, there were their frequent BNF visitors like Wally Gillings, Ken

Chapman, and Ted Carnell. In 1938, the London domicile of

Clarke and Temple, 'The Flat', became the natural gathering place for the science

fiction crowd as well as the paralleling B.I.S. group, and the propaganda, fanzines

and space journals were published with the help of all. That house, at 88 Gray's

Inn Road, Bloomsbury, near the British Museum, was remarkably like a mirror of the

fannish world of the Futurians' co-operative Brooklyn apartment, 'The Ivory Tower'.

The two places were each a magnet for the active sf fans in their greater

metropolitan areas. Over here were Don Wollheim, Fred Pohl, Richard Wilson, Dirk

Wylie, Doc Lowndes, Cyril Kornbluth and more. Over there, besides Clarke and Temple

and Maurice Hanson, there were their frequent BNF visitors like Wally Gillings, Ken

Chapman, and Ted Carnell.

Although Arthur doesn't drink

alcoholic beverages, pubs have always been meeting places for sf fans and Arthur's

writings, both fannish and professional, have acknowledged that reality. In the

early days, sf fans would regularly gather at the Red Bull pub. But the most

inspirational pub was the White Horse, fictionalized by Arthur as 'The White Hart',

which was just off newspaper row on Fleet Street in the heartland of 'The City'. It

was well patronized by both his B.I.S. cohorts and the sf fans and readers. By the

1970s, when I lived in the U.K., the fannish watering hole had shifted to The Globe.

Once a month there would be meetings where newer fellows mixed with the older fans

from the `30s -- an ongoing miniature convention which attracted many out-of-town as

well as out-of-country visitors. A most memorable occasion was when Arthur showed

up, direct from the U.S., proudly showing everyone his latest technological gadget,

a hand-held calculator made by Hewlett-Packard, a remarkable innovation which he was

among the first to own. Although Arthur doesn't drink

alcoholic beverages, pubs have always been meeting places for sf fans and Arthur's

writings, both fannish and professional, have acknowledged that reality. In the

early days, sf fans would regularly gather at the Red Bull pub. But the most

inspirational pub was the White Horse, fictionalized by Arthur as 'The White Hart',

which was just off newspaper row on Fleet Street in the heartland of 'The City'. It

was well patronized by both his B.I.S. cohorts and the sf fans and readers. By the

1970s, when I lived in the U.K., the fannish watering hole had shifted to The Globe.

Once a month there would be meetings where newer fellows mixed with the older fans

from the `30s -- an ongoing miniature convention which attracted many out-of-town as

well as out-of-country visitors. A most memorable occasion was when Arthur showed

up, direct from the U.S., proudly showing everyone his latest technological gadget,

a hand-held calculator made by Hewlett-Packard, a remarkable innovation which he was

among the first to own.

I was in England for seven continuous

years starting in 1970 and grew quite close to the Clarke family. Unfortunately for

me, Arthur was mostly in Sri Lanka then, but I developed an exceedingly close

relationship with his brother, Fred W. Clarke. The Clarke family home was originally

in Somerset, but 88 Nightingale Road in North London had become the headquarters and

home for the two brothers and for Arthur's world-wide activities, as managed by Fred.

I first met Fred and Mother Clarke at the historic professional joint appearance of

Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov in London, in July 1974, at that pair's

entertaining verbal sparring match which resulted in the whimsical 'Clarke-Asimov

Treaty'. Although Arthur is the more experienced world-traveler, Fred has been to

America and Sri Lanka many times. He and his wife Babbs have attended worldcons on

both sides of the Atlantic and have visited my home in Potsdam, New York. Like his

older brother, he has boundless energy, is a public speaker, and is involved in

numerous local and international projects, all the while handling Arthur's archives,

public relations, and their Rocket Publications company. I was in England for seven continuous

years starting in 1970 and grew quite close to the Clarke family. Unfortunately for

me, Arthur was mostly in Sri Lanka then, but I developed an exceedingly close

relationship with his brother, Fred W. Clarke. The Clarke family home was originally

in Somerset, but 88 Nightingale Road in North London had become the headquarters and

home for the two brothers and for Arthur's world-wide activities, as managed by Fred.

I first met Fred and Mother Clarke at the historic professional joint appearance of

Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov in London, in July 1974, at that pair's

entertaining verbal sparring match which resulted in the whimsical 'Clarke-Asimov

Treaty'. Although Arthur is the more experienced world-traveler, Fred has been to

America and Sri Lanka many times. He and his wife Babbs have attended worldcons on

both sides of the Atlantic and have visited my home in Potsdam, New York. Like his

older brother, he has boundless energy, is a public speaker, and is involved in

numerous local and international projects, all the while handling Arthur's archives,

public relations, and their Rocket Publications company.

It was Fred who organized an

elaborate (and six months early) 75th birthday celebration for his brother in their

town of Minehead, Somerset, in July 1992. Arthur had come home from Sri Lanka for a

week. An elaborate Space Exposition had been arranged by Fred, and Arthur, of

course, had a full schedule of lectures and appearances. I had hitched a U.S. Air

Force ride to Mildenhall Air Base, north of Cambridge, to attend the week-long

Festival, and was a guest of the Clarkes at the small hotel in Minehead -- they

stayed there, too, even though Dene Court, the current Clarke country home at

Bishops Lydeard, was not many miles away. The old Clarke home at 13 Blenheim Road

bore the historical plaque which had been dedicated by the Mayor. It was Fred who organized an

elaborate (and six months early) 75th birthday celebration for his brother in their

town of Minehead, Somerset, in July 1992. Arthur had come home from Sri Lanka for a

week. An elaborate Space Exposition had been arranged by Fred, and Arthur, of

course, had a full schedule of lectures and appearances. I had hitched a U.S. Air

Force ride to Mildenhall Air Base, north of Cambridge, to attend the week-long

Festival, and was a guest of the Clarkes at the small hotel in Minehead -- they

stayed there, too, even though Dene Court, the current Clarke country home at

Bishops Lydeard, was not many miles away. The old Clarke home at 13 Blenheim Road

bore the historical plaque which had been dedicated by the Mayor.

A book could be written about that

exciting week end, with so many things going on and so many people met. Two

prominent sf writers were there, old and new -- Bob Shaw, my long-time friend, and

Terry Pratchett, a stranger. I saw Bob briefly for a moment and then was disturbed

and extremely pained, after a frantic unsuccessful search in order to invite him to

dinner and the inner workings, to learn he had abruptly left town for an obligation

I know he could have delayed. Assorted scientists and B.I.S. types were everywhere.

There were fans there too, of course -- mostly Arthur's, but only a handful that

were known by me. A book could be written about that

exciting week end, with so many things going on and so many people met. Two

prominent sf writers were there, old and new -- Bob Shaw, my long-time friend, and

Terry Pratchett, a stranger. I saw Bob briefly for a moment and then was disturbed

and extremely pained, after a frantic unsuccessful search in order to invite him to

dinner and the inner workings, to learn he had abruptly left town for an obligation

I know he could have delayed. Assorted scientists and B.I.S. types were everywhere.

There were fans there too, of course -- mostly Arthur's, but only a handful that

were known by me.

The most amazing moment for me was

at the intimate hotel dinner table with Arthur and family, when Arthur noticed me

squinting through the crack between my thumb and forefinger. "What are you doing?"

he asked. The most amazing moment for me was

at the intimate hotel dinner table with Arthur and family, when Arthur noticed me

squinting through the crack between my thumb and forefinger. "What are you doing?"

he asked.

"Focusing on the tiny printing of

the menu," I said. "Focusing on the tiny printing of

the menu," I said.

"Oh," he said, "does it work?" "Oh," he said, "does it work?"

I'm still bewildered. How could he

suggest not knowing that one could focus light rays that way? It was the only time

ever that I didn't feel inferior to him. I wrote down a couple of quotes from my

memory book at the time: Fred Clarke: "That was a week that was! Wonderful to see

so many friends at one time from all over the world. Especially Dave!" And Arthur

Clarke: "How about Bellefontaine in 2001? Where is [and he named my former Gnome

partner]? Do you have him under lock and key? ACC" I'm still bewildered. How could he

suggest not knowing that one could focus light rays that way? It was the only time

ever that I didn't feel inferior to him. I wrote down a couple of quotes from my

memory book at the time: Fred Clarke: "That was a week that was! Wonderful to see

so many friends at one time from all over the world. Especially Dave!" And Arthur

Clarke: "How about Bellefontaine in 2001? Where is [and he named my former Gnome

partner]? Do you have him under lock and key? ACC"

True to the enthusiast that he still

is, Arthur honors the pulps of yore. He recalls "stories brimming with ideas," and

says they "amply evoked that sense of wonder which is or should be one of the goals

of the best fiction. Science fiction is the only genuine consciousness-expanding

drug." The value of science fiction to Arthur is demonstrated by his observation

that space pioneers such as Tsiolkovsky, Oberth, and von Braun wrote space science

fiction as a means of conveying their ideas to the general public. True to the enthusiast that he still

is, Arthur honors the pulps of yore. He recalls "stories brimming with ideas," and

says they "amply evoked that sense of wonder which is or should be one of the goals

of the best fiction. Science fiction is the only genuine consciousness-expanding

drug." The value of science fiction to Arthur is demonstrated by his observation

that space pioneers such as Tsiolkovsky, Oberth, and von Braun wrote space science

fiction as a means of conveying their ideas to the general public.

There's little doubt that the

monumental motion picture 2001: A Space Odyssey will be Arthur C. Clarke's

world-wide defining event. I've already reported {{ There's little doubt that the

monumental motion picture 2001: A Space Odyssey will be Arthur C. Clarke's

world-wide defining event. I've already reported {{ ed. note: in Mimosa 16 }} about the production set

at Boreham Wood Studios during my 1966 English visit when I first met Stanley

Kubrick and he didn't meet me (because he was so engrossed directing a scene).

What did he have to say about his one time collaborator? He thought Arthur's

artistic ability was unique -- imaginative, knowledgeable, intelligent with a

quirky curiosity, but "Arthur is not an anecdotal character." ed. note: in Mimosa 16 }} about the production set

at Boreham Wood Studios during my 1966 English visit when I first met Stanley

Kubrick and he didn't meet me (because he was so engrossed directing a scene).

What did he have to say about his one time collaborator? He thought Arthur's

artistic ability was unique -- imaginative, knowledgeable, intelligent with a

quirky curiosity, but "Arthur is not an anecdotal character."

It was Bill Temple who hung the tag

of 'Ego' on Arthur. Bill wrote a famous humorous sketch entitled "The British Fan

in His Natural Haunts" in which he teased his good friend Arthur unmercifully. To

this day, 'Ego' Clarke revels in the appellation, even putting out short personal

newsletters called 'Egograms'. I've never heard anyone use that character

description to his face, although I've detected it from time to time as reflective

of envy and derision. No wonder -- Arthur loves to talk about his life, discoveries

and adventures. He often seems to be overwhelmingly immodest and boastful. The

uncomplicated fact is that Arthur is indifferent to any appearance of

self-aggrandizement -- he is simply an unrelenting enthusiast. His interests are

unbounded and his mind is superactive. At any opportunity, whether with a worldly

personage or an enthralled teenager, Arthur will whip out his photographs of some

current activity or opine on a new idea, bubbling with expressions of his keen

feelings. It was Bill Temple who hung the tag

of 'Ego' on Arthur. Bill wrote a famous humorous sketch entitled "The British Fan

in His Natural Haunts" in which he teased his good friend Arthur unmercifully. To

this day, 'Ego' Clarke revels in the appellation, even putting out short personal

newsletters called 'Egograms'. I've never heard anyone use that character

description to his face, although I've detected it from time to time as reflective

of envy and derision. No wonder -- Arthur loves to talk about his life, discoveries

and adventures. He often seems to be overwhelmingly immodest and boastful. The

uncomplicated fact is that Arthur is indifferent to any appearance of

self-aggrandizement -- he is simply an unrelenting enthusiast. His interests are

unbounded and his mind is superactive. At any opportunity, whether with a worldly

personage or an enthralled teenager, Arthur will whip out his photographs of some

current activity or opine on a new idea, bubbling with expressions of his keen

feelings.

Those who understand him know the

spirit and essence of Arthur Clarke, with his deeply-rooted connection to fandom

and its early sense of wonder. He's never lost that youthful exuberance. He's been

to Buckingham Palace. He's received the C.B.E. (Commander of the British

He's been knighted by The Queen. However, he is not merely SIR Arthur C. Clarke --

he is Arthur C. Clarke, FAN. Those who understand him know the

spirit and essence of Arthur Clarke, with his deeply-rooted connection to fandom

and its early sense of wonder. He's never lost that youthful exuberance. He's been

to Buckingham Palace. He's received the C.B.E. (Commander of the British

He's been knighted by The Queen. However, he is not merely SIR Arthur C. Clarke --

he is Arthur C. Clarke, FAN.

All illustrations by Kurt Erichsen

|